The sun seemed to never set on the British Empire, until it finally did. As the spirit of liberation enveloped Africa in the 1960s, the British reluctantly acknowledged that the writing was on the wall.

One by one, nations across the continent tasted freedom from decades of European colonialism. But while the writing may have been on the wall by the 1960s, the proverbial pen had been dipped into the ink at least a decade before.

Following the bloodbath that was the Second World War, a conflict that saw Africans fighting for and dying on behalf of their imperial overlords, independence was eagerly sought across the continent.

Slowly but surely, those who had been ruled from London fought and won their liberation from the British Empire, starting with Ghana who won theirs in 1957. The nation of Uganda would have to wait another five years, but on October 9, 1962, the day would finally come.

The first head of state of the newly-independent Uganda would be Muteesa II, the Kabaka (King) of the Buganda Kingdom. His short rule only lasted three years, before he was overthrown by Milton Obote. But Muteesa II’s road to rulership was not an easy one.

When the British Empire first arrived in the country now known as Uganda, they found not a united nation, but a region sprawling with many independent kingdoms. Of these many kingdoms, the one that the British sought to establish a relationship with was that of the Buganda.

As such, the name of the country ‘Uganda’ was taken from the name of this kingdom, whose administrative capital of Kampala was to become the capital city of the nation. The Buganda Kingdom has a rich history, with records dating back to the 14th century.

It’s first Kabaka (King of Buganda) was Kato Kintu, with the kingdom still ruled by his descendants to this day. The reign of one of his descendants, Kabaka Mwanga II, coincided with the European so-called ‘Scramble for Africa’, and one primarily characterised by steadfast opposition to British imperialism.

After being forced to accept the Buganda’s status as a Protectorate of the British Empire, Mwanga II launched an anti-colonial war against the British. But after being defeated in Buddu, modern-day Masaka District, he was exiled to the Seychelles.

He was to spend the rest of his days there, where he was starved and tortured to death by British soldiers. Tension between the British and the people of the Buganda Kingdom continued to simmer, and eventually, it reached a boiling point during the reign of Mwanga II’s grandson, Kabaka Muteesa II.

When the British proposed a colonial federation in East Africa, Muteesa II wanted the Buganda Kingdom to secede in order to maintain its independence. In response to this, the British Government withdrew its recognition of him as Uganda’s native ruler – under Article 6 of the 1900 Uganda agreement – and he was promptly forcibly deported to the UK.

There is little information about his time spent in London. It is known that he lived at 28 Orchard House in Rotherhithe, South East London, but only a handful of letters survive. Many detail his correspondence with British representatives during his time here.

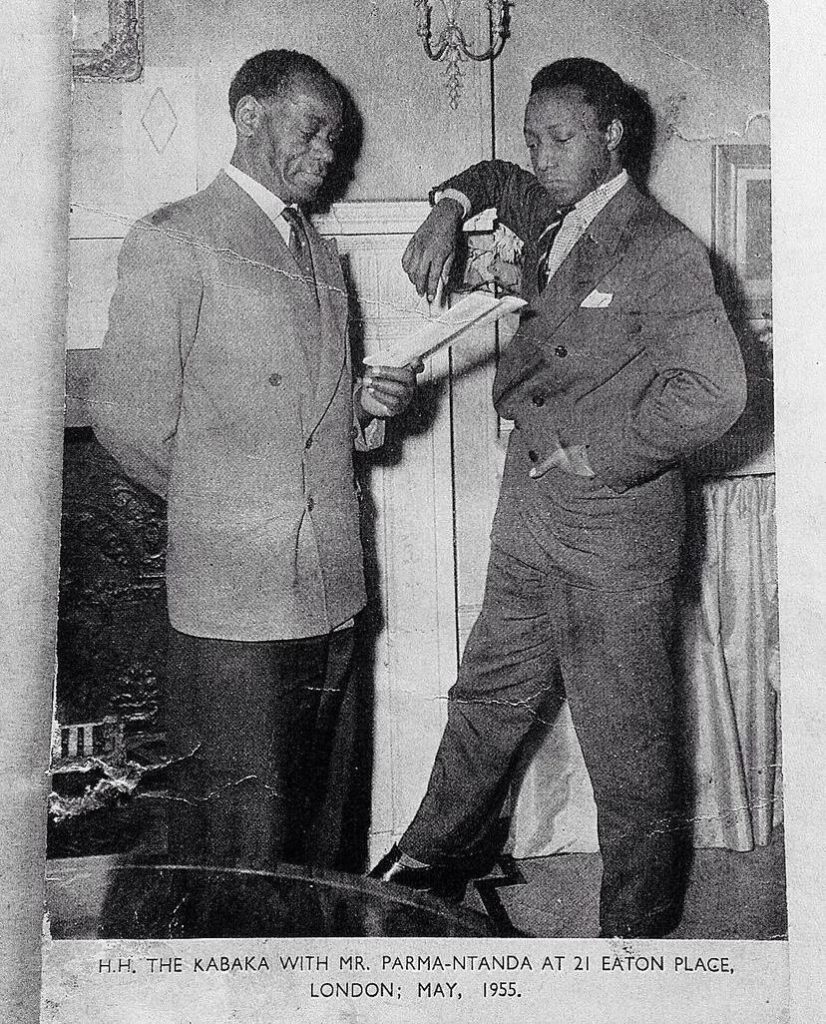

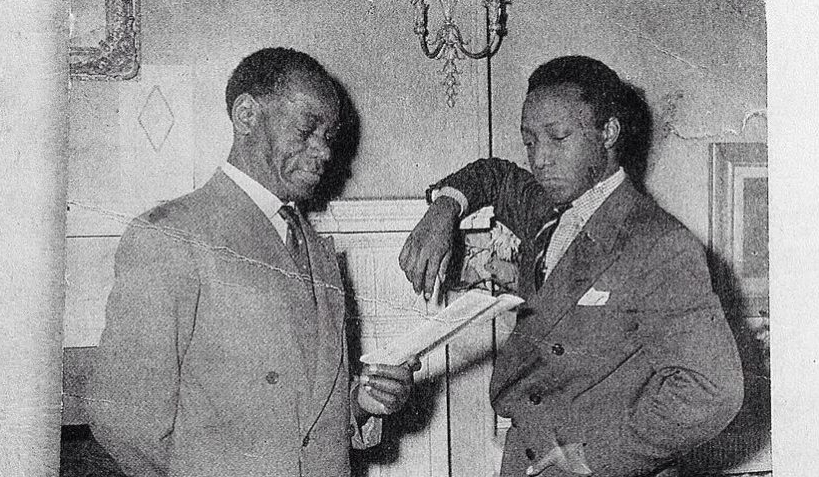

There are few images of him in the city, but one that does survive shows him standing dressed in a suit, with his arm rested casually against a fireplace. He is accompanied by a man who is known to history as Musa Parma-Ntanda. But to me, he is my great-grandfather.

There is very little information about my great-grandfather, Mr Musa Parma-Ntanda. But one thing I do know is that he was trusted enough by the Kabaka to accompany him during his exile to the United Kingdom.

I also know that he was appointed by the Queen of the Buganda Kingdom to represent her and the Baganda Women’s League in London. One piece of documentation that survives of him is an account to British colonial officials he wrote on her behalf.

As part of his preparation for one of his meetings with the officials, he is said to have written the following:

“Up to now, the Kingdom of Buganda has never even been for a day without a Kabaka… throwing the country into chaos.

“From time immemorial the Kabaka has been the heart of the social structure of the Baganda, and his removal disrupts the whole nation.

“The people regard him with the same esteem and devotion as the British people do their own Sovereign.

“He is accessible to his people, meets many of them during tours of his Kingdom, and redresses their grievances and listens to their problems. In matters of tradition and clan precedent, his word is final.

“All the people of Buganda support their Kabaka and are against the action taken by the Governor and the Colonial Office.

“The Baganda are determined to appoint no successor, and continue to recognize Kabaka Mutesa in spite of his banishment.”

His words here serve as a testament to the importance of the Kabaka to life within his Kingdom, and the disrespect felt by those within it at his treatment by the British.

But the fact that it was him, my great-grandfather, who was trusted by the monarch to deliver such an address at what was an unprecedented time in the history of the Buganda Kingdom, is remarkable. It must’ve taken a great deal of courage to deliver such unyielding words to the administrators of the most powerful empire the world had ever seen.

I know little else about my great-grandfather. The only other thing I do know for sure is that he was to be a signatory on the will of the Kabaka, who eventually died in Rotherhithe, London.

It is incredible to imagine that a member of my ancestry, from not too long ago, was once upon a time a member of the Royal Court. The idea that he was chosen to speak on behalf of an entire Kingdom, to those who sought its demise and humiliation, fills me with an immense sense of pride.

Public speaking and journalism go hand-in-hand. You can only hope to get so far as a newsreader if the idea of speaking in front of others fills you with dread. But I am confident that I will never face a task so daunting as to speak to colonial officials on behalf of people who had become the focus of the empire’s conquest.

(Featured image credit: Ham Mukasa Family Collection, digitised by History in Progress Uganda)

Join the discussion