Often characterised by unpredictable bounces and quick kicks, grass tennis courts have long been considered one of the sport’s most challenging surfaces to master.

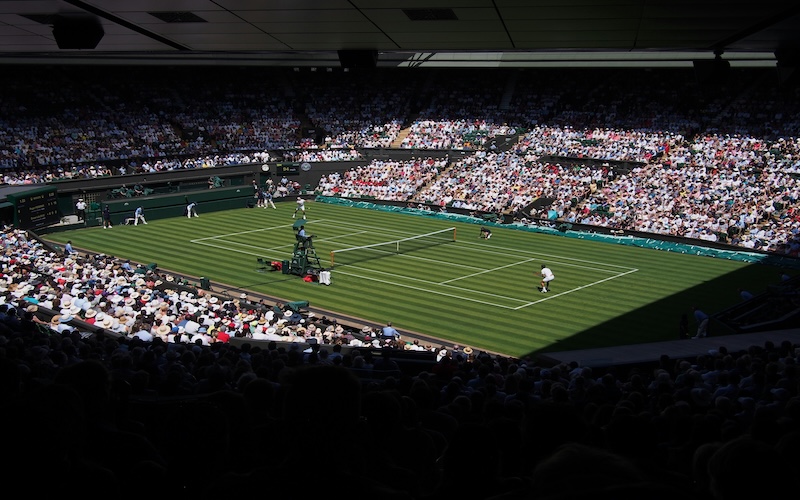

They’re a key reason Wimbledon is widely seen as the most iconic tournament in tennis.

Known for rewarding aggressive styles of play, the surface was once dominated by serve-and-volley specialists like Boris Becker and Pete Sampras.

When discussing changing tactics in grass court tennis, Jeff Sackmann, founder of statistical website Tennis Abstract, said: “It’s been a huge move towards baseline play, definitely.

“If you go back to the 90s, you have Stefan Edberg, Boris Becker, Greg Rusedski and Tim Henman who would serve and volley.

“Now, it’s basically gone.”

One factor which may have contributed to this shift is the fact that tour-level grass tennis courts have now become more durable – a precedent thought to be set by Wimbledon’s change to using 100% ryegrass courts in 2001.

Previously, the All England Club used only 70% ryegrass.

Speaking on the famous switch, Co-Head Coach of Wigmore Lawn Tennis Club in London, Scott Davies, said: “Although before this change, the grass courts were faster, their durability was worse.

“So they’d start off really fast, and then they’d wear down and become way more unpredictable. They’d have slow patches and fast patches, bad bounces.”

The modern grass tennis court, thanks to ryegrass and improved maintenance, plays flatter and more reliably, somewhat resembling hard courts in pace and bounce.

This has caused some players and fans to believe that grass courts have slowed down in recent years, according to Tennis View Magazine.

Therefore, the assumption that grass courts are the fastest on tour may have become somewhat outdated.

But how could these speed changes be measured?

When discussing strong indicators of surface speed, statistician Sackmann said: “Aces are great and basically, it just tells you how well the returner is able to respond. And that’s going to be something influenced by the surface speed.”

While rally length is also considered to be a valuable tool for measuring surface speed, Sackmann believes both produce similar results.

Tennis Abstract’s surface-speed metric uses ace rates to compare court speeds across ATP events, not just the Slams, indirectly factoring in external elements, such as temperature, humidity, wind, the balls used, and of course the physical surface.

A score of 1.25, for example, indicates players would hit 25% more aces on a certain tournament’s surface than the tour average for that year, therefore suggesting a significantly faster court.

According to this measure, the gap between court speeds has narrowed since 1991, compared to 2023, particularly between grass and hard courts – perhaps a result of the use of ryegrass.

However, clay courts, with their naturally higher friction, remain the slowest by a wide margin.

Still, recent statistics from Grand Slam tournaments show that grass courts continue to offer an advantage to powerful servers.

In 2024, Wimbledon, which is currently the only major to be played on grass, produced the highest number of combined aces across both the men’s and women’s draws.

Their ace leaders, Giovanni Mpetshi Perricard (115) and Elena Rybakina (39), accumulated 154 aces between them, a fraction of the 6455 struck across the tournament.

By contrast, at the 2024 US Open, which boasted the second-highest tally for male and female ace leaders at the last four slams, only 3139 aces were tallied – less than half of Wimbledon’s count.

While Perricard, standing at 6ft 8in with a huge serve, could be considered something of an outlier, his run to the fourth round at Wimbledon, which was his best Slam showing to date, illustrates how players with a similar toolset can excel on grass.

These numbers challenge the growing belief that grass courts have slowed in recent years.

In fact, ace rates on grass, as well as across all surfaces, have significantly increased since 1991.

Data collected from the ATP Tour’s top 40 serve leaders shows the average number of aces per match on grass has risen by approximately 76%, from 7.6 to 13.4, between 1991 and 2024 (when the last grass court ATP-level tournaments were held).

While these numbers demonstrate a potential rise in grass surface speed, further blunting arguments that the courts are in fact slowing, these numbers may reflect broader developments in the sport.

Factors such as improved equipment and more intense training regimes have enabled players’ to improve their athleticism – possibly resulting in increased ace numbers.

Discussing advancements in the game, tennis coach, Davies, said: “Players have sports scientists, sport nutritionists controlling pretty much every aspect of their lives.”

Stats connoisseur Sackmann also acknowledged the growing role of fitness in the modern game.

He said: “Now, if you’re if you’re playing almost anybody on tour, even somebody who’s not a great returner, they’re going to make you fight for it.”

Overall, while grass courts can still be regarded as the fastest on tour, the perception that the three main tennis surfaces have become homogenised in recent years could be explained by improvements in player conditioning and court quality – causing tennis to enter an era dominated by baseline play.

Featured Image Credit: Shep McAllister via Unsplash