Ellie was at Waterloo station when a man approached her and asked whether she liked threesomes. He continued loudly asking about her sexual preferences.

There were people around her, but they just stared. “I felt pure embarrassment, and I just wanted to disappear,” she said.

In a separate incident on a train, a man was asking around a carriage for money. When he got to Ellie*, he sat down opposite her and asked her for cash multiple times, but she had none, so said ‘no’.

“He stood up and called me a f****** slut. The other men stared at me like I’d done something wrong,” she said.

Ellie is not alone. Reports of sexual offences increased by 11.3 per cent on London public transport from 2023 to 2024, with 628 offences reported from January to August 2024 compared to 564 reported during the same period the previous year, according to TFL data. While this data includes more serious offences, reports of harassment on transport have also increased.

A 2024 survey by the British Transport Police found a 50 per cent rise in violence against women and girls on trains from 2021 to 2023.

Additionally, the most recent TfL Customer Pulse survey found 34 per cent of respondents had felt worried on public transport in the past three months and 6% of Londoners were completely or temporarily deterred from using public transport due to experiencing a worrying incident.

Of those who were concerned about their safety, 41 per cent said it put them off but they would still travel, and 13 per cent said it stopped them travelling temporarily. Around 5 per cent said it stopped them using public transport completely.

Ellie continued: “I was on the way to a monthly training when the incident happened, so now I find myself a bit wary getting on the train. It is almost as if I am on the lookout for the same guy.

“It made me so uncomfortable the amount of times he asked me in comparison to the men, and the fact that they stared at me when he insulted me. I don’t think the disruption escalated to the point where I thought ‘someone help me’ but when I received the insult it was quite horrible feeling stared at as if I had done something terribly wrong.”

Recent TFL data found the most crimes were reported on the Central line, with 1,419 crimes reported between January and August 2024. This made up 17.3 per cent of total crimes on the Underground.

The most unsafe station was Kings Cross St Pancras, with 359 reports of crime, 4.7 per cent of the total reports.

Another woman travelling alone, Leia*, said: “A man on the escalator kept calling out to me, and followed me on to the train, sitting right in front of me and staring at me. I use a walking stick as a mobility aid and I feel more vulnerable with it. It was very uncomfortable.

“It was a bit scary and made me feel uncomfortable. I’m still uncomfortable travelling in London alone, and I won’t do it in the dark.”

In an instagram poll of 50 respondents, 41 per cent had been harassed or assaulted on London public transport, and 59 percent avoided traveling or felt unsafe on transport following the incident.

Two in five (40 per cent) had witnessed someone else experience harassment or assault on public transport, and 62 per cent said they didn’t know what to do or how to help.

The bystander effect: why don’t people intervene?

Both Ellie and Leia were surrounded by bystanders when they experienced harassment, but no one stepped in to help. People turned a blind eye, or stared at them as if they’d done something wrong.

Lasana Harris, professor of social neuroscience at University College London, explained that to step in, bystanders must register an incident as a “helping situation” and feel competent to assist.

“It might be the case that people expect to see harassment on trains, and so they don’t register that this is something much more serious, but see it as normative,” he said, adding that people take cues from others around them and are less likely to step in if no one else does.

He also noted “diffusion of responsibility” as a factor, where bystanders may realise help is needed but may think somebody else has already helped, so there’s no need for them to do anything about it.

Harris highlighted the phenomenon of “dehumanised perception” where people fail to register others as people – something that is common in cases of sexual objectification.

“When women are sexually objectified, the men who view them as such typically fail to register them as full human beings. When you register someone as a full human being you register that they require help, and it triggers empathic responses. So if you’re objectifying the woman, you may not register that they require help,” he explained, noting that bystanders may objectify the target of harassment because of how she is dressed.

Harris emphasised the importance of education, as many people accept the behaviour as typical, meaning it becomes normative. “Raising awareness around the fact that this is dangerous behavior is important, but also then giving people clear, actionable things they can do so they feel safe intervening,” he explained.

“I think there are also some broader issues around how women are viewed, and gender issues that are relevant here as well that need to be tackled at a societal level so that such behavior doesn’t seem normative,” he said, adding that there is “a lot of work to be done there”.

The importance of being an active bystander

A survey by Rail Delivery Group and British Transport Police found that over three quarters (79 per cent) of UK adults would feel relieved if someone intervened or helped in any way whilst they were experiencing sexual harassment on public transport.

Leyla Buran, campaigns and policy manager at White Ribbon, a charity engaging men in ending violence against women, said harassment and violence against women has been seen as “something only women need to solve or speak out about for too long”, emphasising that men should be “actively part of the solution”.

“Many men want to live in a society where the people they care about, including partners, daughters, sisters, mums, and friends, can go about their lives without fear, which is great, but it’s important to remember that all women deserve to feel this way, not just those we know personally,” she said, noting that even the smallest action can make a difference.

She explained that allyship means challenging harmful attitudes, calling out sexism and ‘banter’, and noticing when someone is shrinking into themselves because of someone else’s behaviour.

“You don’t have to be a hero, but you do have to care,” she added, outlining that actions can be as simple as checking in with someone, changing seats, or defusing a situation with a question that diverts attention.

“Your actions, even small ones, can help create a safer environment for everyone,” she said, adding that “change begins by simply not going along with it”.

‘See it, share it, save her life’

Mia* was travelling by tube when another lady noticed a man was photographing her bare legs. The lady confronted him and asked him to delete them, but Mia didn’t know if he did. He didn’t leave, so she moved carriage.

“I felt a bit awkward and paranoid on the tube afterwards. I felt like I was in shock, and it made me feel objectified and used and gross in a way I haven’t felt before, for example when I have been catcalled,” she said.

Talisker Alcobia Cornford, founder and CEO of Urban Angels, heard countless similar stories shared on university Facebook pages, motivating her to create a safe space where women could share experiences of harassment in their area.

“People would say ‘this guy followed me home’ or ‘this happened to me in this club’, and I noticed it was quite prevalent, but the posts were getting lost a lot of the time, and there were men in the comments invalidating their experiences,” she said.

Within a week of creating the Exeter page, a space for live alerts so that others could avoid unsafe individuals or areas, 1000 women joined. The response showed her the prevalence of the problem. Now, the charity’s groups have over 21,000 members, operate in seven cities, and have 30 volunteers.

Their ethos is centred around stopping assaults before they happen – women can report individuals or areas where they feel unsafe in real time so others can avoid them. “A lot of the time predators don’t go for the first person they see. They look for a victim that’s maybe on their own, maybe looks lost or more vulnerable. Also typically with perpetrators, it’s not the first time that they’ve committed some type of harassment or crime,” Cornford explained.

TfL encourages active bystanders

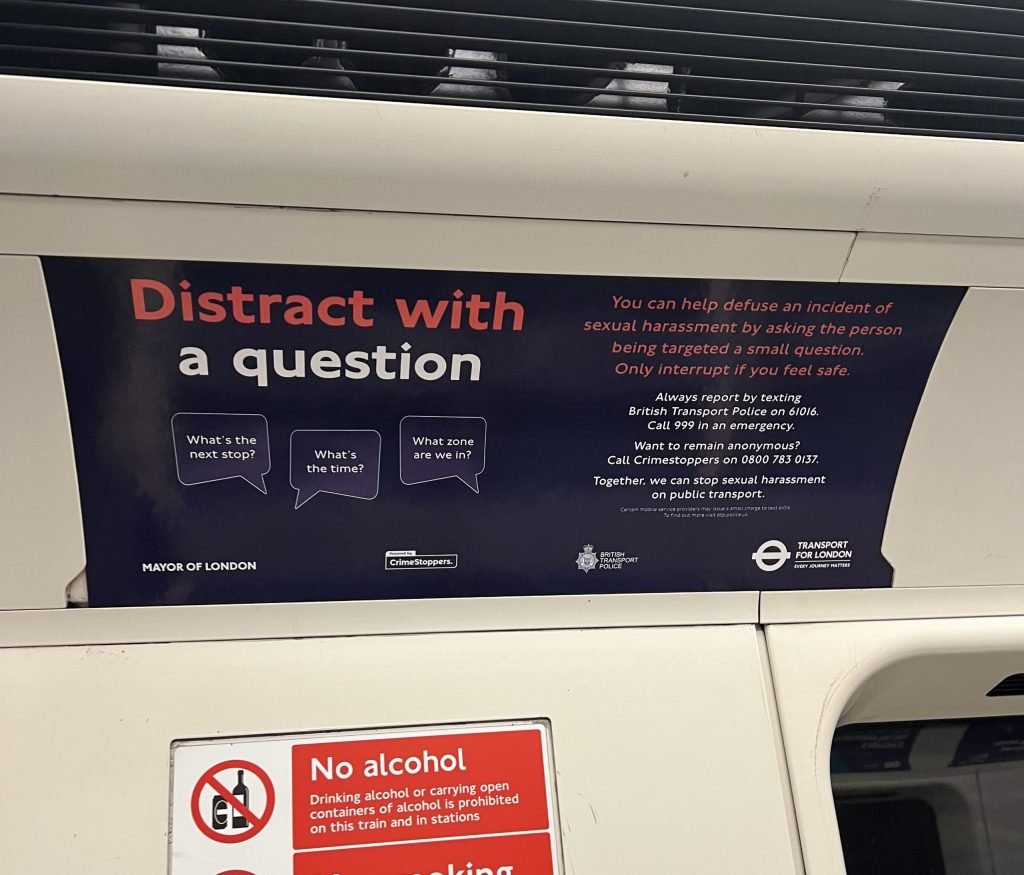

In January 2023 TfL launched a campaign to encourage bystanders to step in when they witness harassment, and to ‘distract with a question’.

TfL clarified they were not asking members to “police the network”, but were giving clear steps to safely intervene if passengers witnessed an incident.

London’s Deputy Mayor for Transport, Seb Dance, said the campaign aimed to send a “strong message to offenders that sexual harassment will not be tolerated on TfL’s services”.

TfL research showed 63 percent of passengers would feel more confident in intervening in an incident if they had more information on how to help.

A TfL spokesperson told SW Londoner: “We want everyone to feel safe when using public transport. The risk of being a victim of crime on our network is low, but verbal abuse and harassment is sadly still a common experience. It is our job to police the network, encourage reporting and have effective security in place. However, we know that people want to support one another if someone is being victimised.”

They explained that the campaign to prompt bystanders to intervene has been “well received”, with an increase in customers agreeing they have all the information they need to confidently intervene. It also continues to generate discussion about the issue.

TfL research found 57 per cent of customers thought they had all the information to confidently intervene in incidents of harassment in 2024, rising from 53 per cent in 2022.

For Ellie and Leia, questioning why no one intervened, more must be done. While ultimately women should be safe to travel without the threat of sexual harassment, Cornford and Buran agreed that in the meantime bystanders have an important role to play so the default response is no longer silence and stares, but action.

If you were affected by any of the issues raised in the article, help is available.

London Survivor’s Gateway, helping victims of sexual assault: https://survivorsgateway.london/

NHS guidence after rape or sexual assault: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/sexual-health/help-after-rape-and-sexual-assault/#:~:text=You%20may%20need%20time%20to,examination%20as%20soon%20as%20possible.

Rape Crisis UK: https://247sexualabusesupport.org.uk/

*Names changed to protect anonymity.