King’s College London students have called for greater awareness and support for those living with hidden disabilities, as mental health difficulties continue to rise among young people in the UK.

Hidden disabilities include conditions such as ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, chronic fatigue syndrome and migraine.

While neurodivergent conditions such as ADHD and autism are not mental health disorders in themselves, research shows people with these conditions are significantly more likely to experience anxiety and depression.

According to Mind’s Big Mental Health Report 2025, one in five adults in England is living with a common mental health problem.

In April 2025, 18% of UK adults aged 16 and over reported experiencing moderate to severe depressive symptoms.

Young adults are most affected, with 26% of those aged 16–29 reporting moderate to severe symptoms, compared with 20% of those aged 30–49 and 18% of those aged 50–69.

While national statistics highlight the scale of mental health challenges among young adults, students at King’s College London say the reality on campus can feel even more complex.

Their experiences show how these trends play out in day-to-day university life, from attending lectures to navigating support services.

Sakina, 20, a King’s College London student, said she does not believe the university is doing enough to support students with hidden disabilities.

She said: “The short answer is no, especially if a disability is invisible or masked.

“You have to prove yourself or put yourself out there by asking, and not everyone feels comfortable sharing their personal circumstances in order to get the help they need.”

The social sciences student lives with chronic fatigue syndrome, chronic migraines and ADHD.

She said fluctuating and masked conditions are often misunderstood: “People assume what they’ve seen from me once on a good day is what they can expect all the time.

“Sometimes that just isn’t possible.”

Sakina also said she has noticed a troubling view towards accessibility measures: “I’ve been seeing more of an attitude equating accessibility with laziness or slacking.

“That is really troubling.”

She explained that even attending classes can sometimes be one of her biggest challenges.

Naz Kaynakcioglu, 22, who studies Clinical Neurodevelopmental Sciences at KCL, shared similar concerns: “I feel responsible for not being visible.

“If I sit in a priority seat or use disabled toilets, I feel like a spectacle.

“I know most people are not thinking badly of me, but I’m already an anxious person.”

She said she is tired of always explaining herself.

Naz is autistic and has generalised anxiety disorder and hypermobility spectrum disorder.

She said constantly having to explain herself is exhausting.

The 22-year-old also described university life as isolating at times: “A university as big as King’s can get extremely lonely.

“We have many societies and student groups, but they can still feel transient.”

Naz said she was quickly signposted to a King’s Inclusion Plan (KIP), which records a student’s disability-related study needs and recommended adjustments.

However, she believes the system is not always effective in practice: “Some lecturers, in my experience, don’t always appear to engage with KIPs, and that defeats the purpose.

“Others are not educated enough on certain things – more training would be helpful.”

Sakina added that neurodivergent students can be taken less seriously than those with visible or physical conditions: “In terms of getting a KIP for neurodiversity only, I might not be best placed to answer, because my physical conditions are generally taken more seriously.”

She also raised concerns about the Disabled Students’ Allowance (DSA) process: “A friend applying on neurodiversity grounds got much less approved and a more dismissive attitude than I did.

“I also think certain neurodivergence and mental health issues are taken more seriously than others.”

Despite their concerns, both students stressed that their experiences did not reflect all staff or departments at King’s.

In England, the proportion of adults screening positive for ADHD has risen from 8% in 2007 to 14% per cent in 2023.

Experts believe this reflects increased recognition and help-seeking rather than a true rise in prevalence.

However, wait lists for assessment and support remain long, and there is no consistent national data on ADHD service waiting times.

Data by NHS Digital shows that common mental health conditions increased in prevalence from 16% in 1993 to 23% in 2023/4 among 16 to 64-year-olds.

Prevalence of severe common mental health condition symptoms has also increased from 9.3 % in 2014 to 11.6 % in 2023/24.

Naz said the requirement for an official diagnosis creates further barriers: “It can take years before students can access support.

“Everyone deserves the support they need before they reach a point of crisis or burnout.”

Young people are also facing wider social pressures.

A recent survey found that 82% of young people in England feel anxious about war and politics, and 87% about climate change.

Naz said she found support through the Disabled Student Society at KCL: “In a society like this, it’s easier to meet people who understand what you’re going through.

“People are getting diagnosed later now, so no one judges you for not having a formal diagnosis.”

She added that disability services staff are supportive but overstretched: “This is not their fault at all.

“I think the university needs to provide more funding – waiting times can be three months, which is really discouraging.”

Despite this, she praised the clarity of the application process once a student discloses a disability.

Naz said: “It’s straightforward once you make it known, the team are very happy to help.”

Sakina believes a wider cultural shift is needed: “There needs to be a serious attitude change in how staff view attention, effort and engagement.

“Nobody should have to announce that a disabled person is in the room for staff to speak in a way that doesn’t marginalise students.”

She added: “Treating disabled students like slackers, implicitly or explicitly, should be recognised as ableism.”

Naz said her ideal support would be proactive and inclusive: “We should work on making everything more accessible for everyone.

“Support should be there without people having to look for it and we need more quiet spaces that aren’t the library.

“University is so loud.”

Both students emphasised that their experiences reflect personal perspectives and that support at King’s can vary widely between departments and individuals.

A spokesperson for King’s College London said: “We want our students to thrive at King’s and we are always grateful for them sharing their experiences and feedback.

“Hidden disabilities and mental health support is an important part of our support programme at King’s, and our academic staff receive regular training as well as guidance to ensure that teaching and learning practices are inclusive and proactive.

“Every faculty also has dedicated Disability Liaison Advisors and Student Support Officers to ensure that students have the support in place to help them to succeed – including working with staff to put in place needs and adjustments outlined in personalised support plans (King’s Inclusion Plans).

“We are proud to be able to help more students than ever to get the right support for them, having recently invested in our resources, and that the University Mental Health Charter Award has recognised the care we take over our students’ wellbeing – we know that there is always room to go further, and welcome feedback that helps us to do so.”

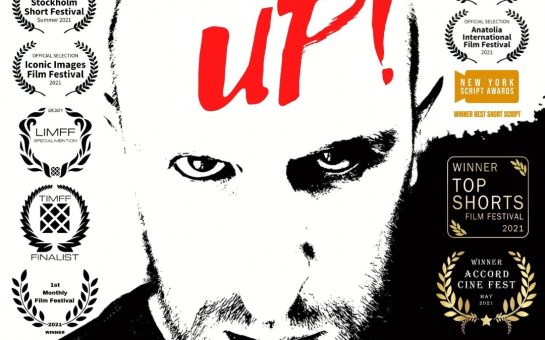

Feature image: Photo by Markus Leo on Unsplash