London’s public toilets are set to be extinct by 2105, according to new research published by online bathroom retailer Victorian Plumbing, an issue that is replicated across the UK.

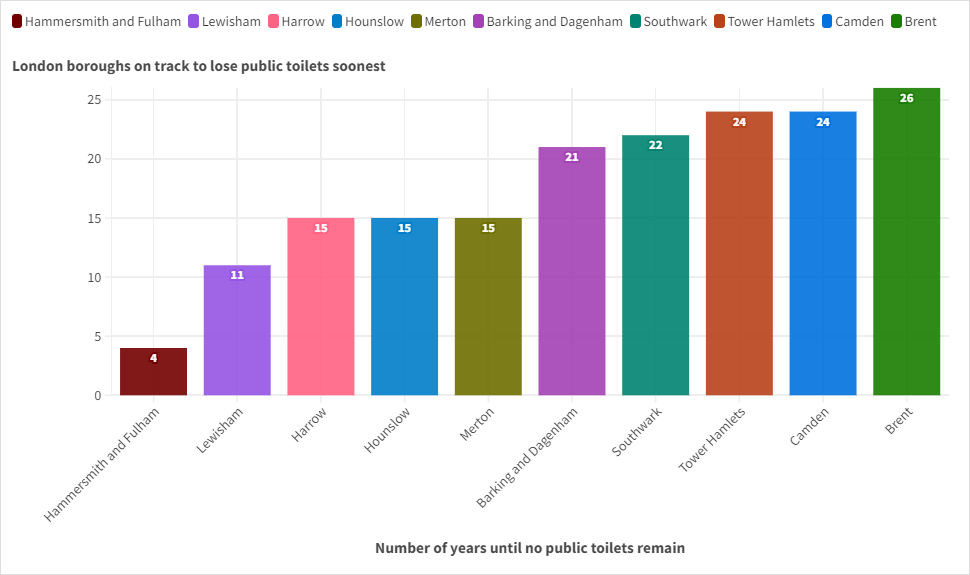

The statistics for the capital lay out that public toilets could be extinct as early as 2028 for Hammersmith & Fulham borough.

The London borough second in line to lose its public toilets is Lewisham, which is expected to have no public toilets by 2035.

The data follows wider trends across the UK, which has seen the number of public toilets fall drastically in recent decades.

Raymond Martin, managing director of the British Toilet Foundation, estimates that half of the UK’s public toilets have disappeared in the last ten years.

The rates of decline have been the topic of discussion for health societies and charities for a number of years, with numerous petitions being launched to stop the closure of public toilets and calling on local councils to properly fund these spaces in their areas.

In May 2019, the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) published a report into the growing issue titled – Taking the P*** – The Decline of The Great British Public Toilet.

The report breaks down the health impact of declining public toilets and the public’s view on this issue as well as recommendations on how to solve the crisis.

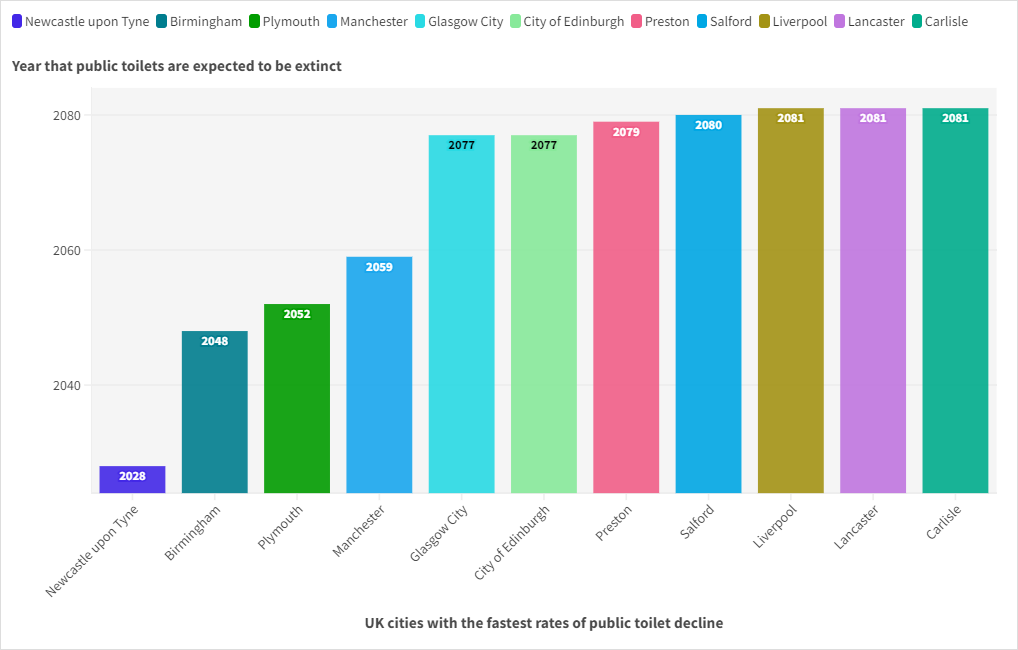

As research from Victorian Plumbing would suggest, however, this issue doesn’t seem to have improved in the last five years, with data suggesting that at the current rate of decline, Newcastle upon Tyne is set to be the first city in the country to have no public toilets available, in just four years.

Multiple cities across the country are facing the same eventuality, with the scale of the problem being a nationwide issue.

Why are public toilets disappearing?

The RSPH’s report found that the reason for a dwindling number of public toilets across the UK is due to a lack of funding due to cuts to local authority budgets.

The closure of public toilets during national Covid-19 lockdowns also left many facilities unmaintained for months at a time, with some never reopening, and this played a role in fast-tracking the extinction of the public toilet in the UK.

Surprisingly, public toilets are not something that councils or governments are required to provide in Britain.

There is no statute enshrining the right to access toilets from a health perspective or otherwise in the UK, with Wales being the only country in the UK to recently introduce a new Public Health Act that requires local authorities to publish a strategy for local toilets in their area.

What are the impacts?

Why are campaign groups and members of the public fighting so hard to overturn the decline of public toilets?

RSPH’s report noted three key issues for the health impact of a declining public toilets: ‘the loo leash’, the issue of ‘holding it in’ and the question of sanitation.

The loo leash refers to the restrictive effect that a lack of public toilets has on a person’s ability to access public spaces.

Those with medical conditions that have a more frequent need for the toilet, in the cases of diabetes, prostate or bowel conditions and some disabilities, may be reluctant to socialise in the local community because they know that they will struggle to find a toilet.

The impact that this has on people’s lives is isolating and alienating, especially in a post-Covid era where the need for connection and community has proven to be so important.

Lewisham resident Rhiannon Suchak, 27 said: “I didn’t realise that there was such a drastic decline of public toilets. That’s very, very debilitating for people who rely on public toilets, disabled people or people who depend on that when they go out.

“It’s not really an issue just of the actual public toilets in an area because if people don’t feel comfortable and safe going out that’s going to have a knock-on effect on their physical and mental health as well.”

When surveyed by the RSPH, more than half (56%) of respondents said that they restrict fluid intake in case they can’t find a toilet when out and about.

Although commonly practiced, this can be detrimental to health over time, as well as exacerbating medical conditions that are already present.

Just a few of the health effects of deliberate dehydration are: headaches, weakness, dizziness, increased risk of renal stones and reduced short-term memory.

Fewer public toilets can pose serious sanitation issues in some areas, particularly when street-urination and defecation is practiced as a result.

This problem can be especially present near parks, green spaces and city centres in the evenings in areas where outdoor drinking is more common.

As well as being off-putting, poor sanitation can pose a particular risk to young children and people in wheelchairs.

With a lack of spaces available for hand washing combined with busy areas where people are eating on the go, there is an increased risk of contamination by pathogens, contributing to the spread of epidemics – an unwelcome situation, especially in the context of a population recovering from Covid-19.

The report also published data on the reasons why people don’t use public toilets, with more than 60% of women and 40% of men citing concerns about smells and cleanliness.

Suchak added: “I don’t think I’d use public toilets over pubs because they’re never normally that nice. They probably smell, maybe they’re not clean, maybe there’s no toilet paper, which I guess says something about the funding towards them.”

So what can be done?

The decline of the great British public toilet has not gone unnoticed.

People across the country have launched petitions calling on the government and local councils to provide more public toilets, opposing the scales of closure that they have seen in their local areas.

On Change.org alone, a simple keyword search of public toilets will retrieve petitions from Abergavenny in Wales and Cork in Ireland to Wandsworth.

In some cities, local campaign groups have sprung up in the face of further public toilet closures and organised protests and demonstrations.

Just south of London in 2023, a local petition to Brighton and Hove City amassed a huge 8579 signatories on Change.org after the council announced plans to permanently close down as many as 18 of the city’s public toilets.

The decision was eventually scrapped, but only after a persistent campaign fought by locals. A separate petition on the councils website also received a total of 5223 signatories.

Much of the fight against Brighton and Hove’s public toilet closures was organised by the community union Acorn.

They launched the ‘Save Our Toilets’ campaign, holding rallies outside the cities town hall with local residents and meeting with local councillors to ask for more funding to be directed toward these public spaces.

Speaking to local Brighton newspaper The Argus last year, a spokesperson for the union said: “Public toilets are a basic necessity and councils shouldn’t see them as an expendable luxury. This isn’t just about public toilets – it’s about our ability to exist in and access our public spaces freely.”

Victorian Plumbing, after sourcing the data on the UK’s impending public toilet extinction also filed their own petition on Gov.uk calling on the government to make it law that local authorities must provide public toilets.

The petition states that: “Public toilets are essential for a healthy and inclusive society. They provide a safe and sanitary place for people to relieve themselves, regardless of their income or social status.”

The RSPH’s report has offered a few solutions to the public toilet crisis taking place in the UK.

A priority of the report was to call on the government to ‘reverse years of funding cuts to local authorities and invest in our civic infrastructure’.

The report refers to analysis from the Local Government Authority that showed that local services will face a funding gap of £7.8 billion by 2024/25.

The RSPH also recommended ways for national and local government to source the funding needed to invest in these local services.

The ‘spend a penny’ campaign would draw one penny from the price of every train and bus ticket, instead going towards funding toilets in the local area.

Supporters say that the funding model could be tailored to different regions, estimating that ‘taking a penny on every London bus and tube journey corresponds to nearly 700 fully funded facilities – more than 20 new public toilets for every borough’.

In order to tackle these issues though, the report points to the importance of breaking down ‘the toilet taboo’.

Authors recommended raising the profile of the subject with conferences and collaborations with charities that want to publicise the ‘toilet problem’ with the incorporation of the issue into wider charity campaigns like Red Nose Day, where an emphasis could be made on the health and social impacts of dwindling public toilet numbers.

In February last year a motion titled ‘funding for local government and public toilet provision’ was tabled by eight MPs.

The motion, introduced by Green MP Caroline Lucas, was sponsored by five Labour MPs and later gained the support of Independent MP Claudia Webbe and Labour MP Bell Ribeiro-Addy in October.

The motion stated that ‘this House believes that public toilets are essential social infrastructure, vital for public health and inclusion, and necessary for people with long term conditions, disabilities, young children, homeless people and others of all ages to get out and about’.

Although not a policy commitment, the act of high profile MPs raising the issue in parliament is a significant step.

Campaigners hope that the government will make the provision of public toilets compulsory and well regulated, arguing that they ‘should be considered as essential as streetlights, roads and waste collection, and equally well enforced by legislation and regulations’.