By Joe Ives

August 29 2020, 14.00

Follow @SW_Londoner

Training to help people with severe mental health difficulties can take years to complete.

Yet thousands of prisoners across the county are tasked with providing many of the same services after just a few weeks of instruction, and can be woken in their cells at all hours of the night and called in to help often deeply unwell and sometimes dangerous prisoners.

The Samaritans’ Listener scheme was launched in HMP Swansea in 1991 to create a peer-to-peer mental health support structure within prison walls. A runaway success, it now operates in almost every prison in England, Scotland and Wales.

Like Samaritans volunteers on the outside, Listeners do an essential task, preventing suicide and self-harm through confidential and non-judgemental emotional support.

With mental health deteriorating in prisons across Britain, Listeners have seen their job remit expand beyond the scope of any training possible for an inmate.

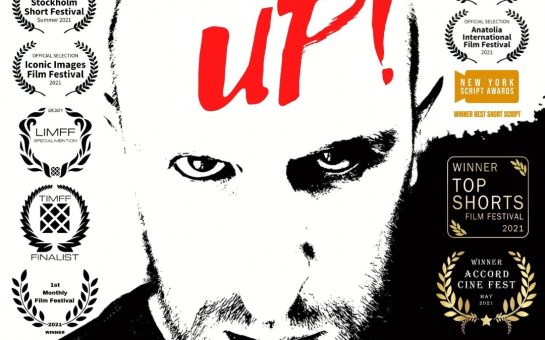

“It’s like sticking a plaster on a shotgun wound,” says Chris Atkins, a filmmaker and former undercover journalist who became a Listener at HMP Wandsworth whilst serving the beginning of a five year sentence for fraud between July 2016 and March 2017.

“We could help a little bit but we couldn’t solve the core problems that were causing a lot of the despair.”

Atkins, who served as a Listener for 9 months, says the majority of the contacts he was helping were people who were severely mentally ill and should not have been in prison in the first place.

Mark Fairhurst, national chairman of The Professional Trades Union for Prison, Correctional and Secure Psychiatric Workers (POA), agrees, citing a need for specialised facilities for people whose mental illness had a strong influence on their crime.

Mr Fairhurst, who has been a prison officer for over 29 years, praised the Listener scheme but called for wider change.

He said: “It’s a very good initiative. It’s been very successful, but the point is that we shouldn’t have to resort to things like that.

“We’re dealing with more and more people with mental health problems and we struggle to meet their needs because they shouldn’t be in a prison they should be in an environment that’s conducive to their needs.”

According to an analysis by the Office for National Statistics, male prisoners are 3.7 times more likely to die from suicide than the public.

At the same time, a recent Ministry of Justice report showed that recorded incidents of self-harm in prisons reached a record high of 64,552 between 2019-2020.

This translates to 777 incidents per 1,000 prisoners and the latest chapter of an alarming seven year upward curve.

A House of Commons committee report cited staff shortages, insufficient mental health diagnoses and support, an outdated prison estate and prevalence of synthetic drugs as key reasons for the crisis in Britain’s prisons.

Atkins says the Samaritans do their best to support Listeners. However, with the scale and severity of severe mental illness in British prisons today, they face an almost impossible task:

“The training was very good, but there wasn’t training for ‘right, here’s how you spot a psychotic episode’, ‘here’s how you know someone needs more medication’, ‘here’s how you see the difference between schizophrenia and ADHD’ – there wasn’t any of that.”

The former prisoner and author, whose book A Bit of a Stretch: The Diaries of a Prisoner outlined many of the failings he saw during his time in HMP Wandsworth, said: “It’s a vicious circle. There’s only so much a Listener can say in that situation. They can help a little bit, but the core problems go way above our heads.”

Being on the frontline can take a heavy toll on Listeners.

“Talking to someone who has just cut their arm or talking to someone who is telling you how they are going to cut their arm, or talking to someone who is hearing voices in their head telling them to kill everyone – it’s quite intense,” Atkins said.

“Not only are you in the same room as them, you’re locked in and no one has a key.”

“If you want the session to end you’ve gotta hit the light and hopefully the officer will come and if they don’t you’re stuck with them, and that’s at the forefront of your mind – that that door is locked.”

Despite Samaritans offering frequent support to Listeners, such extreme experiences can create a risk of burnout and mental fatigue.

Atkins says speaking to fellow Listeners and writing his diary helped him cope.

Nevertheless, he believes his time as a Listener had an effect on his personality.

“I got very flat emotionally,” said Atkins, who was called out to see up to five people in a single day.

“I didn’t react to what was happening in front of me at all – because you couldn’t.”

Still, he says it has given him a fresh perspective, encouraging him to look for the deeper issues often hidden by angry facades.

Being a Listener can also have its benefits within the social fabric of prisons, conferring respect from prisoners and officers alike.

“As a Listener, you’re quite high up in the pecking order,” Atkins said.

“I was the one person who was going ‘oh my god mate are you alright, let’s talk about what’s upsetting you.’”

Atkins believes change needs to occur at a multitude of levels, including the wider perception of prisons.

He said: “There’s a mentality if you are tough on crime and brutalise people, you will, somehow, stop reoffending.

“The exact opposite is the case.”

Samaritans can be reached 24/7 on 116 123 or via email at [email protected]