Almost 115,000 teachers have left the profession in the last three years for reasons other than retirement, according to new Department for Education (DfE) data.

The November 2024 School Workforce Census, an annual statutory headcount of teachers and support staff alike, showed 114,769 teachers have left the profession over that time period.

The census is filed individually by schools, with the individual figures then nationally collated and published by the DfE’s workforce data.

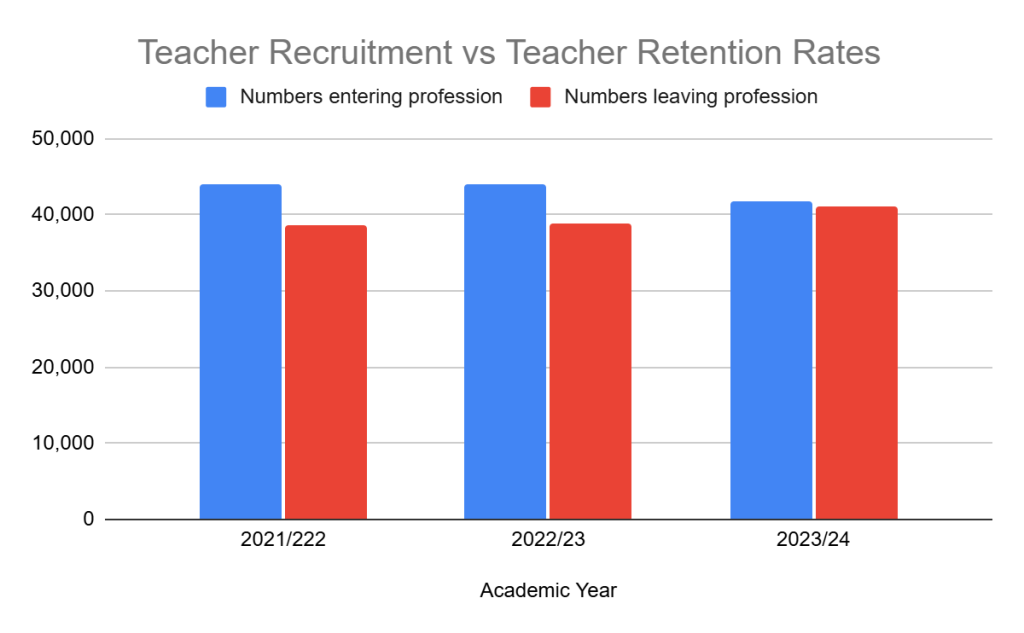

At the end of the 2023/24 academic year, 37,413 teachers left the profession, down slightly from 38,788 in 2022/23 and 38,568 in 2021/22, accounting for around 9% of the teaching workforce.

These figures are an aggregate total and encompass the full range of teachers and teaching assistants across the career continuum, and does not offer a specific insight into retention rates among newly-qualified and early career teachers (ECTs).

This does not include the 11,500 teachers who retired over that same three-year period, either.

Closer examination of the data found tjust over a tenth (10.3%) of ECT teachers quit after one year, while almost a fifth (19.5%) quit after two years, over a quarter (26.8%) quit after three years, and just under a third (32.4%) left after 5 years.

This lends support to the national retention crisis which has been covered extensively in the news as an ongoing issue.

The overrepresentation of ECT teachers in the attrition rates here leads to an automatic finding that teaching remains an unpopular profession for the younger generation, but ECTs include career-changers, and previous homemakers, among others, so is not entirely driven or defined by age.

Figures from DfE’s School Workforce Census count every person who leaves the UK state education sector so does not take into account those who remain in teaching either by opting to switch to the private sector or relocating to countries like Australia and UAE in search of higher salaries and other perks.

Yet for those who have left teaching entirely, the most frequently cited reason, from a range of surveys and research pooled together, was the heavy workload and poor work-life balance which ultimately led to burnout, coupled with pay not deemed commensurate to the workloads.

Unruly behaviour of some children was another commonly-cited reason, as was the excessive micromanagement during the early stage of a career, when all ECT teachers are closely monitored by their assigned mentor and are subject to routine observations.

One anonymous source said: “My head of department (HOD) would spontaneously wander into my lessons outside of my regular required observations and meticulously go through books.

“My HOD would then pull me to the back mid-lesson and flag things that I’d forgotten to tell the kids or reprimand me on their work, in regard to whether they’d copied a definition down or not done enough work.”

Another anonymous source, who is still working in education, said: “It’s not uncommon for students to be bullying staff.

“The long summer holidays are often bandied about as a so-called perk of the teaching profession, but what if I was to tell you that it’s impossible to enjoy any of these holidays as you’re constantly on edge thinking about the back-to-work blues.

“To spend the entire duration of every weekend and half-term mentally replaying previous incidents at the school and anticipating certain behaviours from your usual class culprits for when you return.

“I’m mentally at the school even when I’m not physically there.

“I now take sleeping pills because of the insomnia and sleepless nights that working in this profession has brought me.

“To make matters worse, the parents defend their children, often flipping the script and turning the problem around on me, which means I’m forever fighting a losing battle.”

Bryn Gilwern, a former secondary school teacher of seven years, recounted his time in teaching as something he does not miss.

He said: “The decision to leave was in some ways not really a decision at all, I was compelled to do so by the mental health toll.

“Depression, sleeplessness, heavy anxiety and underlying tension all of the time.

“I dreaded going into work. Sunday evenings were horrific.

“I stayed the course for seven years. What stopped me from leaving sooner was the security of the job in terms of a steady income and a pension.

“But feeling low and miserable all the time doesn’t exactly scream security to me, and once I’d realised this it was simply time to go.”

The NASUWT claimed there has been 30,000 violent incidents against teachers involving students with a weapon, defined as any sort of object, over the last 12 months.

The union also reported a fifth of teachers have been physically assaulted by students in the same timeframe.

A PGCE trainee teacher who was tempted to withdraw from teacher training during her first placement, but had a change of heart on her second placement at a different school, attested to how bad behaviour can be at some schools.

She said: “I had tables thrown at me, chairs thrown at me, pencils thrown at my eye, my car vandalised by students in balaclavas – all while I was heavily pregnant.”

Mr Rufael, former teacher who has taught at seven schools across four different countries, claims that the UK is the worst place to teach.

While these anecdotes give some insight into low retention rates, it is contrasted by teacher recruitment rates.

Indeed, the general flux of teachers entering and leaving the profession each year is roughly at break-even point.

These figures are, in some respects, reassuring to the labour market that the profession is unlikely to ever be saturated in the way that other popular graduate roles are.

A potential reported downside with these tight turnover figures is that it creates a situation where schools have little choice in their selection and appointment of teachers.

In turn, this relative lack of competition for vacancies can be disincentivising in terms of the quality and provision of education.

Even with tight turnover figures, however, teacher-pupil ratios and class sizes are operating well within the statutory minimum teacher-student ratio of 1:30 (one teacher for every 30 students) required for primary schools.

Data from the School Workforce Census, shows that primary schools across the country are operating on teacher-student ratios of 1:20.8 on average.

There are no statutory minimum ratio levels for secondary schools, which have an average ratio of 1:16.7 and where ratios are instead driven by internal risk assessments and individual school policies.

This is also the case for non-mainstream schools such as SEN specialist schools and pupil referral units, where the ratio requirement is driven by age rather than the behaviour or vulnerability of students.

Teacher recruitment being roughly on par with teacher retention perhaps doesn’t provide a full picture if these incoming teachers are unqualified, non-specialist, or have qualified under a different educational system overseas.

The figures provided do not offer a further breakdown or differentiation of the type of teachers joining the profession each year either.

Feature image: Free to use from Unsplash