![]() By Alice Fuller

By Alice Fuller

January 15 2019, 09.49

Follow @SW_Londoner

It’s an inevitable fact – death is coming for us all one day. And yet most of us can’t bear to contemplate it, let alone talk about it.

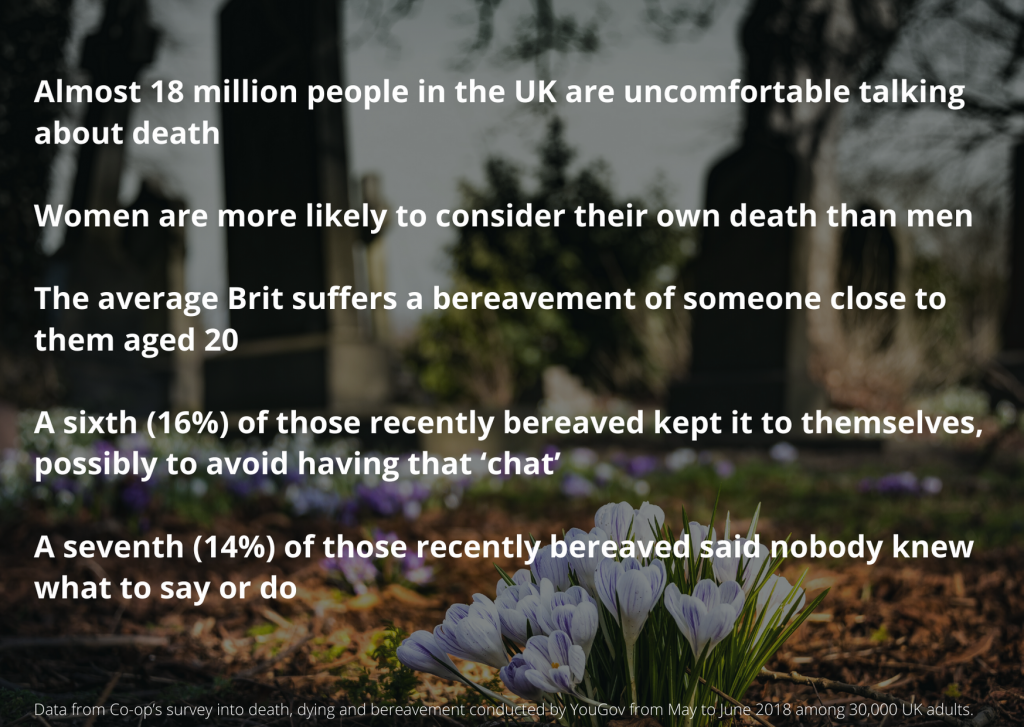

Almost 18 million people in the UK are uncomfortable talking about death, according to 2018 Co-op data.

But attitudes are slowly shifting.

Comedy TV shows like Ricky Gervais’ After Life and weekends devoted to the topic like Good Grief Festival are helping to open the conversation and make the inevitable slightly less scary.

And people are also tackling the issue in their own communities.

One such initiative is the Lewisham Death Café.

The name might be enough to send most Londoners running for the hills, but according to the Café leader Francis Gardom, 86, it’s a warm and welcoming place.

“This isn’t a bereavement session – it’s a get together in a café, eating cake, while happening to have a common interest in discussing death and dying.

“We spend far more time laughing than we do crying,” he said.

Francis founded the group four years ago after facing the death of his wife Anne Carmelita.

He said: “I was married for 50 years and then bereaved, so I’ve had that experience.

“Both my parents died when I was young – my father when I was only 10. And we had a child die of cot death, so I know something about death.”

Death Cafés sprang up in Switzerland and the idea has slowly spread. Each café is designed to create a safe and confidential place for people to express their thoughts on death and dying.

“When I discovered Death Cafés, it was exactly what I was looking for,” said Francis, who is a clergyman at St Stephen’s Church in Lewisham.

He believes people need to be more open to talking about death and says Death Cafés are the perfect way to start.

He said: “I hadn’t met people who had been willing and eager to talk about death, not just from a philosophical point of view but a practical one as well.

“There isn’t any other way to easily bring up the subject at a dinner party. They all say, ‘oh how morbid.’

“People just don’t want to think about it and yet it’s one of the two shared experiences everybody has to go through.”

Francis discovered the Death Café movement through a newspaper advert.

After experiencing five different groups, he decided to set up his own.

The Lewisham Death Café, which meets monthly, is advertised as a place to meet new friends and discuss things people often find difficult, even impossible.

Francis’ role is to ensure people stick to the rules – no evangelising – and to be there for anybody who gets distressed, which according to Francis, very rarely happens.

January was Lewisham Death Café’s 51st meeting and the discussion ranged from the cost of funerals to how long is acceptable for a road to close following a fatal accident.

Frank Jurksaitis, a regular at the Lewisham meeting, said: “I got involved because I’m very interested in culture and our search for meaning.

“I’m intrigued by what h Alex Ritchie and Christian Fraser appens to us when we hit the buffers, which may be social, emotional, relational or even physical.”

The meetings have raised questions for Frank, a retired teacher in his mid-70s, he hadn’t considered previously.

He said: “Can we come to the end of grief without eventually betraying those we have loved? What is the right balance of looking forward and looking back?”

We spend our whole lives avoiding so much as mentioning death. And then we wonder why it’s so hard, why the conversations are so awkward, why the grief is so isolating when it happens. Because of course it happens. #Death #DeathCafe #SundayThoughts

— Bridget🦇Nixon (@bridienixon) December 23, 2019

Helen Brewerton, 48, is a palliative care nurse specialist and head of community services at Royal Trinity Hospice, Clapham Common.

She also believes we need to talk about death more often, and that we need to start early.

Helen, from Lambeth, said: “I think society as a whole very much treats death and dying as something that is very abstract, almost something that is never going to happen to them.

“There’s a sort of mystique around it that if we talk about it then it’s more likely to happen.”

Helen believes this discussion needs to start in childhood to help remove the stigma.

She once approached the headteacher of her children’s primary school to see whether someone from the hospice could come and speak to the pupils.

Helen said: “She looked at me like I’d decapitated a cat in front of her. She was absolutely horrified.”

She added: “I have seen for a lot of patients and their families that death hasn’t been talked about until it’s happening.

“It means there is so much more anxiety and difficulty around it, particularly when it comes to ensuring the person who is dying gets what they want.

“This is much more likely to happen if there have been conversations earlier on about it.

“People have an image of dying which is generally developed from watching films and medical dramas like Casualty, but very often, that is not how death happens.”

Royal Trinity Hospice helps patients and families to have what it describes as a ‘good death.’

Helen said: “The concept of a ‘good death’ is an interesting one. There is no one definition of a ‘good death’ – it’s about an individual’s preferences.

“’Good’ is synonymous with peace – it’s about being ready and not feeling frightened.”

Helen credits her job for giving her a unique perspective on death.

She said: “I feel lucky I’ve had so much exposure to it because I understand it’s not as scary as it’s considered to be by the general public.”

Helen, Frank and Francis think it’s time to say goodbye to euphemisms when talking about death.

Forget ‘passed away’ or ‘gone’ – they died and that’s that.