There is a fear which comes from watching an anthology-style play that the structure will expose some scenes as being stronger and some, detrimentally, as being weaker.

In Joel Tan’s new play, Scenes from a Repatriation, that fear could not be more unfounded as it is an absolute spectacle.

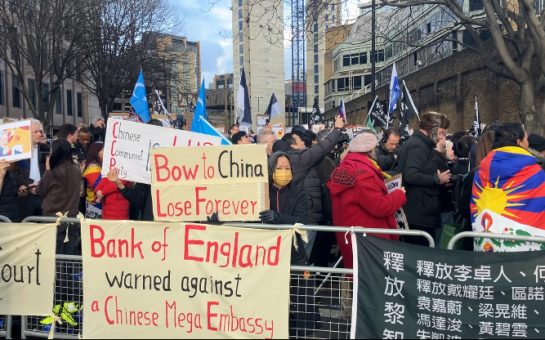

It covers a string of scenes in the repatriation of a Boddhisattva Guanyin from the British Museum to China, including a boycott by Chinese students in London, negotiations with the British Museum, a Q&A with an art historian, a billionaire’s party, and a police interrogation, the whole play bookended with heart-stopping violence.

The structure means that the cast are constantly multi-roling, shapeshifting in age, physicality, and language.

There is not one weak performance in any of the dozens of roles all night, but a special mention must go to Aidan Chen, whose various physicalities and consistently note-perfect comic timing were out of this world.

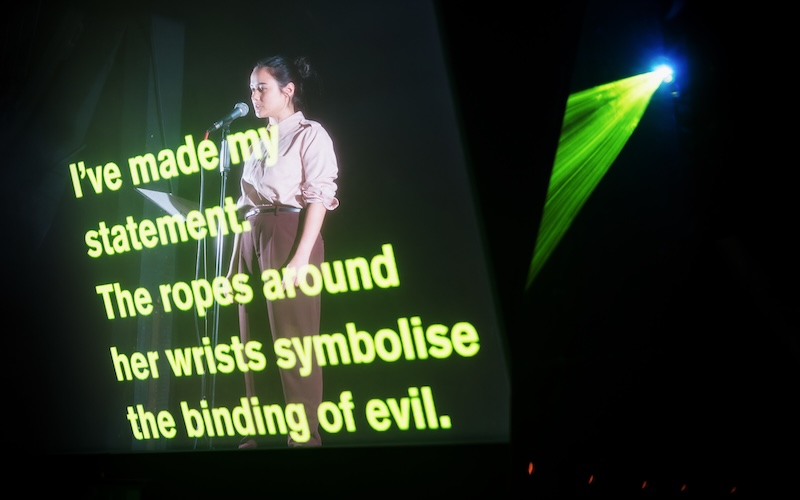

He metamorphosed from a stuffy museum curator, pointedly blowing his vape across the stage to communicate his delicious passive aggression, to a chill-inducing political prisoner in a windowless room in Hong Kong, and a spoken word artist suffering under the conflict between his Chinese heritage and his sexuality, in a speech suffused with bone-dry irony.

The script demanded a great deal of its six actors, flitting between belly laughs and pin-drop drama at the drop of a hat, and it is a testament to Tan’s writing that it came together with such great success.

Tan demonstrated some of the best-executed nuancing I can recall, which is just about the highest compliment I can muster.

No character survived his examination, and no character was wholly good or bad.

His writing of arguments was a particular high point, notably during the meeting between a university professor and her student who is calling for a protest against the British Museum.

Every interruption, interjection, accusation, and explanation told its own story, whether that was a micro-aggression, or a desperate plea to be understood.

The set design, sound, and lighting were also all utterly faultless.

The Jerwood Theatre Upstairs at the Royal Court is not a large space, but every inch was put to use.

The traverse stage was completely submerged beneath sand, while the screen above the entrance become a museum placard at one point and a window to a spiritual communion at another.

Sitting on the front row, I was utterly absorbed into the set, getting splashed with water, having my bare knee pawed repeatedly by the foot of a particularly flirtatious Chinese dragon, and still found grains of sand in my socks hours later.

At the far end from the entrance sat the subject of repatriation, the Guanyin statue, which was entirely swaddled in protective material and rope, so that it was only visible as a vague shape.

Despite this, I found myself repeatedly and subconsciously looking towards her throughout the performance, knowing that I wouldn’t be able to see her.

Yet, at the same time, I wanted to check whether her expression had changed in response to the scene in front of her, such was her presence within the show.

In each scene her meaning shifted, from maternity to homesickness, to patriotism, to separatism, to one last desperate source of hope.

The show was directed by the experimental duo emma + pj with great inventiveness, particularly considering the comparatively small stage space.

The directorial choices felt wonderfully effortless throughout, playing to both sides of the traverse seating without appearing to be too overly-considered.

A particular high point came during the police interrogation scene, performed in Chinese, in which English subtitles were displayed on the screen in front of the interrogator.

This created a sense the dialogue had taken a three-dimensional form in the space, and enveloped the audience in the foreign language in an artful and highly effective way.

Besides being thoroughly gripping, the play was also hugely educational, enlightening the audience on both the history of China and the country’s contemporary issues.

At no point did the script slip into preachiness, or treat its audience as idiots – it was a pleasure to learn from it.

Scenes from a Repatriation is a roaring success for Tan and his team, and a perfect fit for the Royal Court as a bastion of the highest calibre theatrical writing.

Picture credit: Alex Brenner