The decision to close the Lord Ashcroft Gallery at the Imperial War Museum (IWM) last year, understandably, struck a sensitive chord.

The gallery, which displayed a collection of Victoria Crosses and George Crosses – the UK’s highest honours for bravery – had been a fixture of the museum since 2010. Although public outcry delayed the closure by four months, its eventual end was interpreted by some as a snub to courage and sacrifice rather than a museum going about the normal business of rotating its artifacts.

In September, the Daily Mail published a piece by Lord Ashcroft lamenting the gallery’s closure, and the Express reported Lord Ashcroft lets rip at ‘woke’ museum for shutting war heroes medal exhibition.

The businessman, pollster and philanthropist accused the Imperial War Museum of preferring diversity to gallantry, arguing that medals honouring ‘the bravest of the brave’ are being removed from public view to make space for other narratives.

In response, the museum offered a practical explanation, stating that: “Like all museums, we regularly update our galleries to ensure we can share as much of the 33 million items in our collection as possible with the public.”

The IWM says it remains committed to displaying Victoria and George Crosses across its UK sites, placing them in galleries that tell the wider story of each conflict rather than presenting them in one space.

The museum’s Refracted Histories trail, which highlights a number of LGBTQ stories connected to conflict, proved particularly controversial.

In December, the Telegraph reported on the reaction of Lord Ashcroft to the closing of the Victoria Cross collection: Imperial War Museum accused of removing medals to promote trans history: “Lord Ashcroft says museum is ‘beyond parody’ as it launches LGBT history virtual tour.”

A visit to the museum, however, suggested a more nuanced picture; although there were some posters referring to the new digital trail, it actually proved quite difficult to find at all.

After walking twice through the First World War galleries, and finally asking at the information desk where the trail was, the cheerful, but ultimately unhelpful woman behind the desk had not heard of the exhibition and said she did not know where it was.

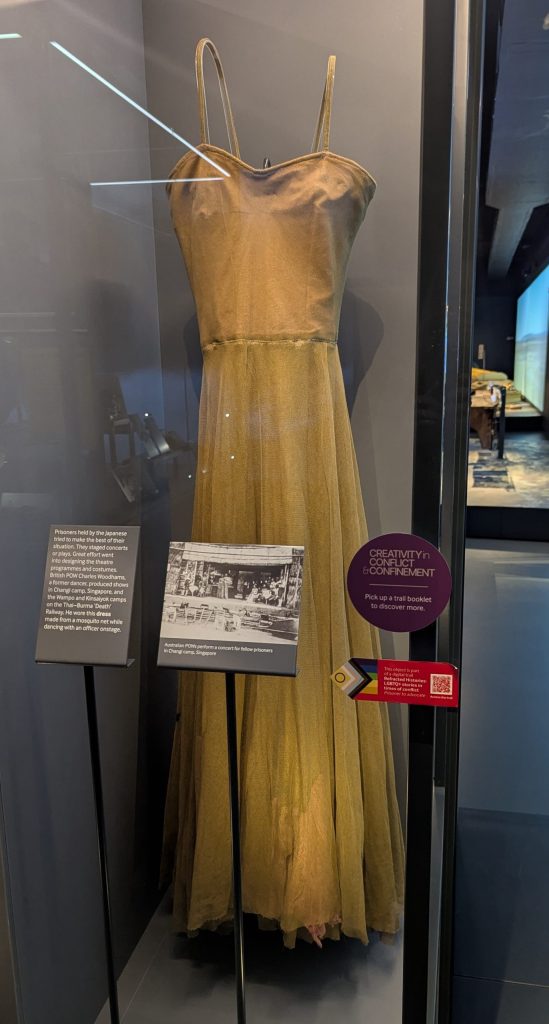

After resuming the search in the Second World War gallery, the much talked about mosquito net dress, worn by prisoner of war of the Japanese, Gunner Charles Woodhams, appeared, nestled alongside other artefacts from the period. Woodhams produced numerous revues at Changi, Wampo and Kinsaiyok, and wore this dress while dancing with an officer in one of them.

Except for a small sticker bearing a pride logo, and a QR code to scan for more information – the digital part – it would be easily overlooked unless you were actually searching for it.

Although the dress has dominated headlines, in the museum space, it sits quietly within the broader narrative of wartime life.

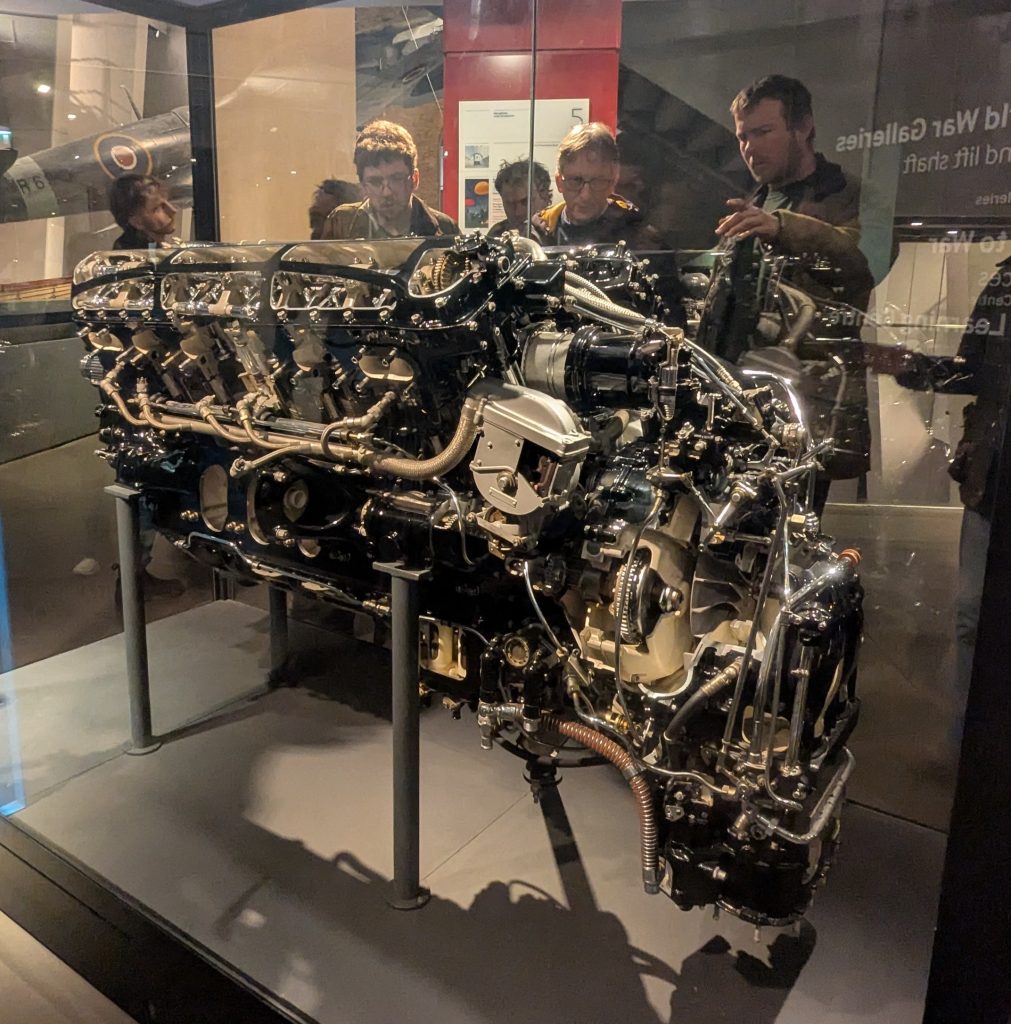

For the most part, the museum remains largely focused on the traditional aspects of conflict that you would expect. The First World War galleries are still dominated by the experience of soldiers in the trenches with visitors able to walk through a life size trench.

The Second World War galleries continue to centre on military conflict, strategy and sacrifice. The Holocaust exhibition is deeply moving.

Meanwhile, Lord Ashcroft’s medals exist now in a virtual version hosted online.

Viewed in this way, a practical difficulty becomes apparent. Compared with tanks that you can touch, aircraft suspended in the museum’s atrium, and case after case of military uniforms and weaponry, rows of medals — however sacred their meaning — aren’t especially interesting to look at in a museum.

Their significance lies almost entirely in the stories behind them rather than in their physical presence. For a museum that relies on getting plenty of visitors through the door, that’s a challenge.

On broadening its scope, the IWM London says that although the past ten years have witnessed new galleries exploring the First and Second World Wars, the Holocaust, and an art, film and photography collection have been opened, displays exploring the past 80 years of post-Second World War conflict, including the Cold War, Falklands War and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, are less well represented.

An IWM spokesperson said: “Our aim is to address this by creating new gallery spaces on upper floors at IWM London, which will allow us to share more stories of conflicts that are within many of our visitors’ living memory.”

For more information about the Imperial War Museum click here.

Featured Image: Imperial War Museum Photo: Cressida Wetton