The Freemasons were thrust back under the spotlight last month when The Metropolitan Police launched a new policy requiring officers to declare Freemason membership.

But concerns about Masonic influence extend beyond the Met.

One former police and crime commissioner candidate, who asked not to be named, told SW Londoner they were greeted with a Masonic handshake by a chief constable during their campaign.

But what exactly are the Freemasons — and why does a centuries-old fraternity inspire such suspicion?

The Freemasons have demanded an emergency injunction from the high court to halt the Met’s new strategy.

The organisation say they are now awaiting the court’s ruling on their application for an injunction, hoping to advance their arguments against the new policy in a judicial review.

They have accused the Met’s policy of amounting to ‘religious discrimination’ and claimed the force is ‘whipping up conspiracy theories’ about their influence, according to The Guardian.

The force says a survey of more than 2000 officers showed strong support for the policy, with 66% of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing that Freemasonry should be included.

The Met’s decision followed a review into the force’s handling of the unsolved murder case of Daniel Morgan.

The 37-year-old father of two was killed with an axe in Sydenham, south-east London, on 10 March 1987.

Ten police officers who were prominent in investigations into Mr Morgan’s murder were Freemasons, according to the report.

However, the panel said it had “not seen evidence that Masonic channels were corruptly used in connection with either the commission of the murder or to subvert the police investigations”.

A London resident said: “I absolutely have concerns about corruption in the Met.

“If you’re in a public service like the police, you shouldn’t be able to keep these things secret.”

The Met’s policy reflects broader questions about transparency in policing, though it remains unclear whether other forces will follow suit.

‘It’s brotherly love’

Shane Stewart, a newly initiated Freemason, spoke to SW Londoner about why he joined — and why the fraternity faces such mistrust.

Stewart’s father was a Freemason.

After his death, Stewart said he struggled to find direction, and began looking for a “big brother” figure and “mentor,” although originally suspicious about the group.

“I just needed to find out what it was all about,” he said.

What he found surprised him.

“It’s brotherly love and a safe space for men to talk — it’s really wholesome. For me, the main thing I’ve gained is the camaraderie. I love seeing the boys, I really do.”

On the Met’s policy, Stewart questions where such declarations should end.

He said: “Where do you go next? There are groups of influence wherever you go, so where do you stop asking people to declare these things?”

But he acknowledges the organisation’s image problem.

“I do think we should be more open about who we are and what we do,” he admits.

“They’re really struggling with numbers — it’s dominated by much older people.

‘I’m not quite sure what the future of the Freemasons looks like’

Freemasonry dates back to the early 18th century, a time of industrialisation and great change in Britain.

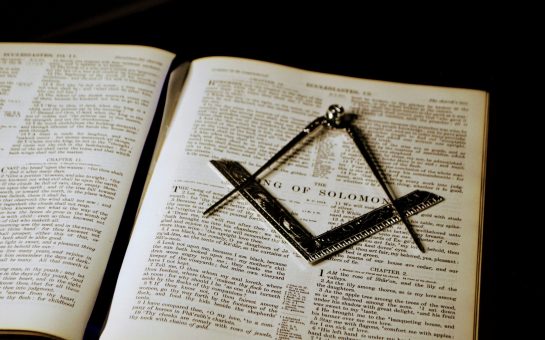

The fraternity linked itself with skilled stonemasons of the past and adopted symbols accordingly, like the all-seeing eye, builders tools, or squares and compasses.

Geometry holds particular importance, with Greek mathematicians Euclid and Pythagoras central to Masonic thought.

A foundational allegory is the building of King Solomon’s Temple, housing the Ark of the Covenant, which contained the original tablets of the Ten Commandments.

The focus is less on Solomon himself than on the process of building the temple — the organisation, sacrifice, and perseverance required — with particular emphasis on the master architect Hiram Abiff.

The organisation is split into smaller units of members, called Lodges.

Today, The United Grand Lodge of England has more than 200,000 members who meet in 6,800 Lodges across England, Wales and the Channel islands, and in a number of Districts and Lodges across the world.

But despite its size and charitable work, the group remains shadowed by suspicion.

With the injunction pending and judicial review looming, both sides are preparing for a lengthy legal fight.

But the deeper question remains: in an era demanding transparency from public servants, can Freemasonry’s tradition of secrecy survive?

Share your views on Freemasonry in policing:

Featured image: New Scotland Yard. Credit: Ian Probets, Pexels

Join the discussion