Children in the UK waited longer in care before being adopted in 2023 than in previous years according to new Government data.

Children for whom an adoption decision had been made had to wait an average of two years and five months.

This figure was up two months from the previous year, and almost half a year more than in 2019.

Chief Executive of Adoption UK Emily Frith said: “The sooner adoption has been decided as the best plan for a child, the sooner they can be placed with a loving family who can offer them permanence and stability.

“There is still far too much delay in the system, as these figures show.”

The data released by the Government records the duration from the moment a child is taken into care until they are adopted.

Why is this happening?

Since the pandemic, the overall number of adoptions in the UK has decreased in all age brackets.

Despite being two years beyond the end of lockdown restrictions, the numbers have not come close to returning to their pre-pandemic levels.

If children are waiting longer in care, by default this means that less adoptions are happening.

The cost of living crisis is one of the main reasons that could explain both the increase in waiting times for adoption, as well as the overall drop.

A survey carried out by Adoption UK at the beginning of 2023 revealed that 87% of prospective adoptive parents said cost of living increases were a serious consideration in the decisions they were making about adopting.

Frith explained: “Some adopters who already have a child have said that they cannot take another child in, whereas they would have in the past.”

Prospective adopters Rita and Kyle* from Sutton had been keen to adopt ever since they got married ten years ago.

They already had two children of their own, aged 11 and seven, but wanted to open their home to a child who needed it.

However, since the onset of the cost of living crisis, they have had to reconsider their plans.

Rita said: “It has been such a difficult time for us, as we really do want to adopt a child.

“But we barely have enough money to look after the four of us at home now, so it would be unfair for us to bring another child into that situation.

“We are still hoping to adopt in the future, but now is just an impossible time for us to commit.”

*names changed to preserve anonymity

Adoption in the UK

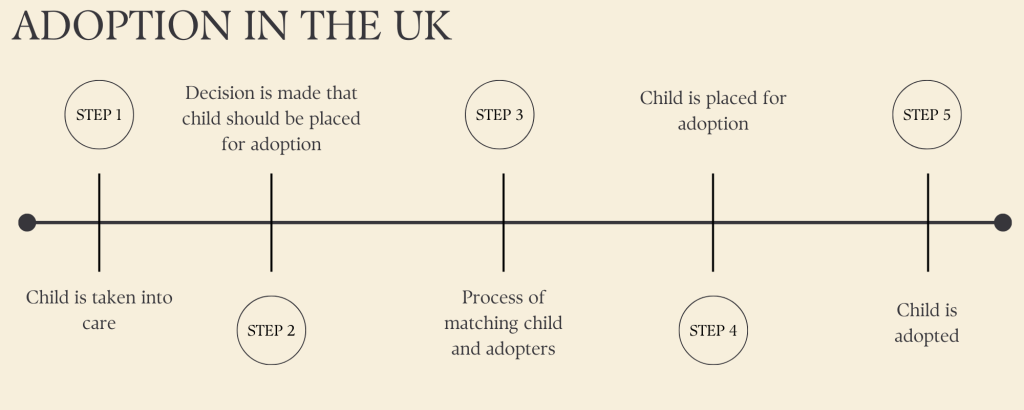

In the UK, most adoptions happen because a child is taken into the care system by authorities.

Social workers then make a decision as to what the best plan for the child is.

Options can include foster care, where a child is temporarily looked after by a family, or a kinship arrangement which is when another family member cares for the child.

However, these are temporary arrangements for children who may be able to be reunited with their birth families.

A decision for adoption is made for children who are unable to return to their birth family.

Once a decision for adoption is made, social workers will match the child with a suitable family from a pool of prospective parents.

During this process of matching a child with family, the child will remain within the care system.

Once a match has been found, the child is then ‘placed’ for adoption, which is when they move in with the adoptive parents.

The final step is for the adopter/s to seek an adoption order.

This means that the adopter gains full legal and parental rights of the child.

An adoptive family can apply for the adoption order once the child has lived with them for ten weeks.

Why is the increase in waiting times important?

The rise in waiting times can have a significant impact on the children in care.

Although the waiting period has only gone up by two months in a year, this extra time can have a detrimental effect on the children in question.

Children in care may experience lots of different foster homes and carers before being adopted.

The number of these types of temporary placements is likely to increase the longer a child is waiting for adoption.

Frith said: “These children are trying to form an attachment, build that bond and have a sense of permanence in their very early life.

“This sense of ‘belonging’ is so important in terms of cognitive and emotional development, yet they are having all this disruption.”

Whilst fostering can provide a temporary and convenient solution, multiple placements can cause uncertainty and distress to children.

A potential solution indicated by Frith is the rise of Early Permanence Placements (EPPs).

With an EPP, a family will foster a child while they are waiting to see if a decision for adoption will be made.

This type of fostering is done with the view that if the decision for adoption is taken, that family will be the ones to adopt them.

But if the court makes a decision that adoption is not the right choice for that child, they will leave the family.

EPPs allow children to have a sense of stability with a single family, rather than being moved around from house to house.

The risk is instead on the family, meaning that more EPPs could provide a solution to the life of young children being considered for adoption.

Firth concluded: “Every day that a child is not with their permanent family is a day lost in terms of building that connection and attachment which is so important in later life.”

Featured Image: Guillaume de Germain on Unsplash. License found here