Brixton in 1981 was a world apart from the rest of Britain.

Reggae music livened every street corner, activism and protests were rife, and police brutality was an everyday occurrence. Each was fundamental to the Black British experience, something the UK would heed for the first time that April as the people of Brixton engaged in all-out war with the police.

Ros Griffiths was 15 when Brixton erupted in 1981, and as the daughter of Caribbean immigrants she endured racism every day. “From the time I enter primary school I am encountering racial slurs and called names. From the age of five,” she said. “People who looked like me were just treated differently, almost as if we were subnormal. We were going through these experiences from the time we could talk.”

Griffiths was part of a new generation of Black British children that the education system didn’t cater to, understand, or respect. “It was not designed for people like myself to thrive, strive, and be successful,” Griffiths says. “They had no expectations.” Teaching was Eurocentric, focusing on the glories of white Britain. Black people only featured as slaves. “So it was all distorted and altered to talk about history that made them look good and us look bad.”

One teacher at her school understood the struggle however. Darcus Howe had come to Britain from Trinidad in 1961 and was a figurehead of anti-racist activism alongside figures like Linton Kwesi Johnson and Farrukh Dhondy, all based in Brixton. “So in my community I grew up with big personalities and activists. It was all around me,” Griffiths says. “They had their headquarters on Railton Road, organising and mobilising.”

Howe and his confidants told stories of the racism they experienced in the 1960s, and Griffiths credits them with sparking her own passion for activism. Growing up Black was not easy, she says, “but through it all I lived in a great community that was resilient and rich in culture.”

Bob Marley was another inspiration, as songs like Get Up, Stand Up resonated with her feelings of suppression. “Reggae music was part of my staple diet,” Griffiths laughs. “As I went to bed, reggae music. As I woke up, reggae music. It was the music of resistance.”

And it was resistance against the police that Brixton became known for. The sus law – sus short for suspected person – allowed police to stop, search, and arrest anyone they suspected might commit a crime, and this usually meant young Black men. “Everybody has a story to tell when it comes to police harassment,” she says. “It was the narrative for Black experience. It was them and us.”

Working together for a safer London.

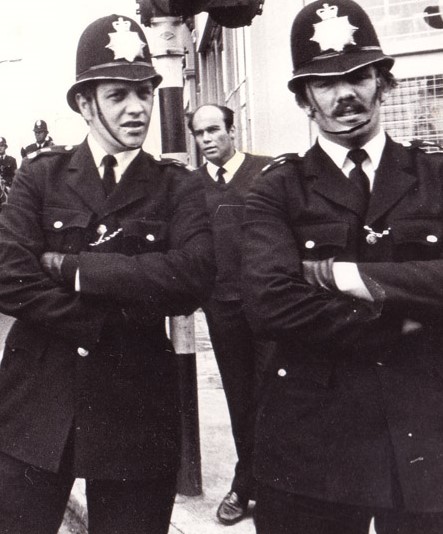

“It was them and us,” are the exact words of Lord Brian Paddick, who was posted as a sergeant in Brixton in October 1980. “It was seen as a problem area.” The basic perception was that “there wasn’t a good person living in the Brixton area,” he says, “and police were united against the common enemy, which was the people of Brixton.” Stop and search was accepted practice and police acted more like an occupying army than protectors of the Brixton community.

Paddick told me about an arrest he tried to make in Brixton Market, where a shopkeeper had reported a theft. “When I tried to arrest the individual concerned I was surrounded by a hostile cry-out who tried to rescue the person from me so that I couldn’t arrest them,” he says. “I had to be rescued by police colleagues from that situation, so that was the degree, or an example, of the hostility.”

In January 1981 Paddick began a year-long college course that combined police studies with academic subjects like sociology and public policy, an experience that changed his entire perspective on the Metropolitan Police. “I went back at the end of the course to the same team that I had been on before, with the same people more or less, and the feeling I got was that they had become racist.” he says.

What Paddick soon realised was that he and his police colleagues had been racist even before he left for college. “I had been so inculcated into the culture of the policing that I didn’t recognise my own racism, and therefore I didn’t recognise the racism of the officers around me,” he says. “Having spent twelve months at police college I realised how racist the officers that I worked with were.”

The revelation for Paddick, however, was common knowledge for Griffiths and other members of Brixton’s Black community. “All I knew growing up, we were told categorically that the police don’t like us,” she says. “They weren’t serving and protecting the Black community. If anything they were harassing us, and what happened in New Cross further cemented my thoughts about the police.”

13 dead, nothing said.

On January 18 1981, a house in New Cross caught fire and 13 young Black people, aged 14 to 22, were killed. Yvonne Ruddock, one of the victims, was having her 16th birthday party. “I was always told that New Cross was a National Front area. It wasn’t an area that they liked Black people,” Griffiths says. A community theatre was burned down three years earlier, for which the National Front claimed responsibility, and a Caribbean house party had been firebombed in 1971. “Black people suffered horrendous forms of discrimination and racial harassment and nothing was done,” she says. Even after a second inquest in 2004, the cause of the fire has not been established nor has anyone been charged.

“The people who died in this fire, they were my kin. They were a similar age to myself at the time so we resonated with that,” Griffiths says. “We had this sense that institutions didn’t care about Black people. Black lives didn’t matter.” The phrase “13 dead, nothing said” became a rallying cry for London’s Black community and its leaders organised a march: the Black People’s Day of Action.

On March 2, a rainy day, between 10,000 and 20,000 Black Britons marched from New Cross in south London to the Houses of Parliament to demand change. “We were the first generation that were born British so we weren’t turning the other cheek like our parents did,” Griffiths says. “We just weren’t having it. We were not going to be called the n-word, told to go home – we’re going to stand up and fight for our rights.” People left their workplaces, their schools. “The teachers heard about the march and they locked the school gates,” she explains, “and we said to them, ‘we’ve got to go on this march so we’ll see you tomorrow.’ So we climbed the gate and we went.”

Griffiths was enthralled by her first experience of activism. After being supressed and mistreated her entire life she felt empowered by the opportunity to stand in solidarity with those who shared her experience. “That was the first time I actually saw that volume of people attending a protest, a demonstration, that looked like me,” she says. “Even if I wasn’t saying anything, just being there I felt empowered. I just felt that I belong. I felt that we’re making a stand. We want something to change, to be treated with respect.” Sadly, however, that respect would not come.

The British character.

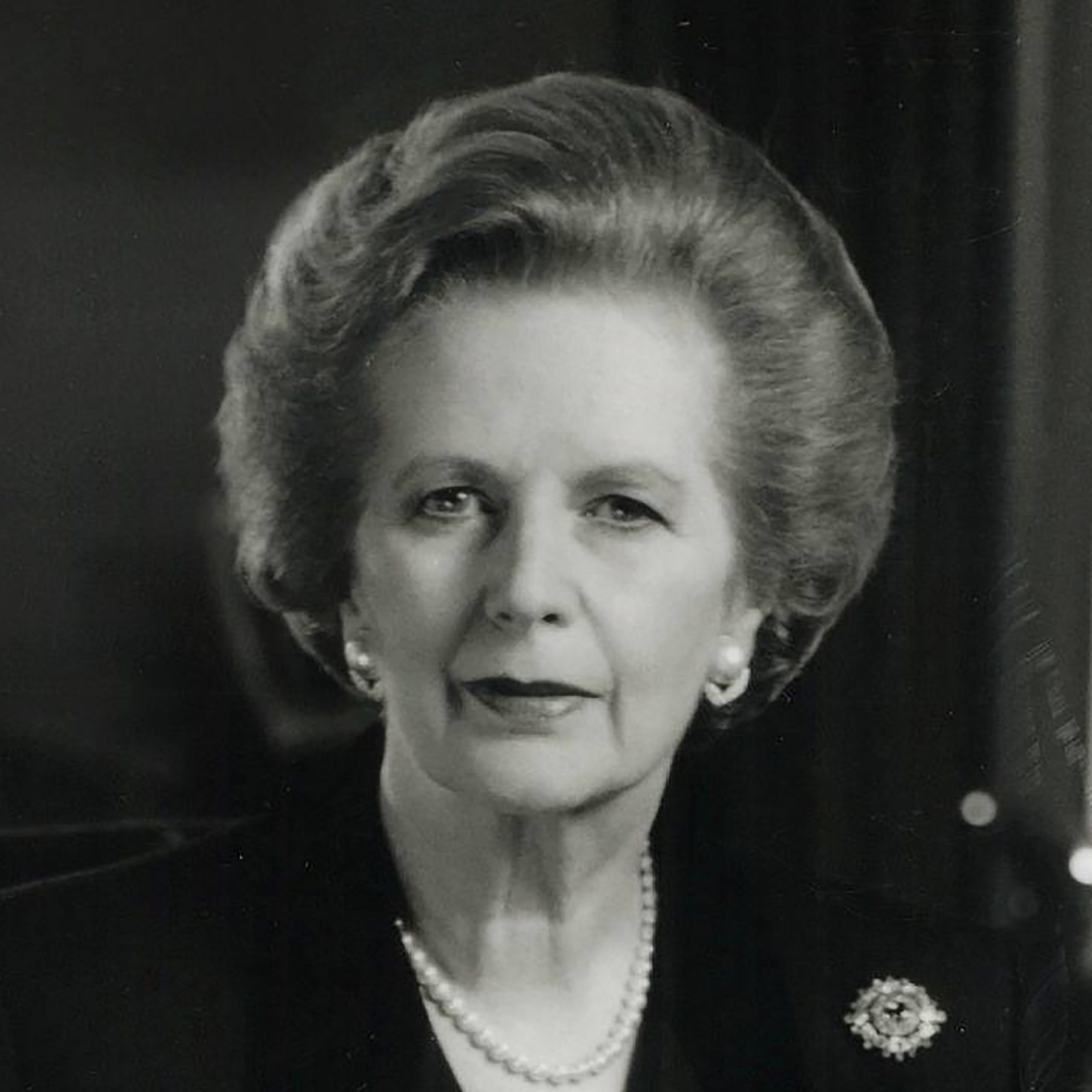

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had given a television interview a few years earlier, on January 27, 1979, which made clear the establishment’s view on immigrants in Britain. “People are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture,” she said. “The British character has done so much for democracy, for law, and done so much throughout the world that if there is any fear that it might be swamped, people are going to react and be rather hostile to those coming in.”

Operation Swamp was launched in April 1981, in which plain-clothes police officers flooded Brixton to stop and search as many potential criminals as possible. Given its namesake, this again meant non-white people. Paddick was heading into Brixton police station for his payslip that Friday evening, and he “was very surprised to see what were obviously police officers in plain clothes on every street corner, and I thought to myself, ‘this really is an army occupation’.” The disguised officers were stopping and searching young Black men every 20 to 30 yards, over 1,000 people in less than a week.

Later that day a Black youth named Michael Bailey was stabbed on Brixton’s Atlantic Road. When he was eventually found by a patrolling police van, blood was pouring from his wound. The officers radioed for an ambulance but Bailey kept resisting. The ruckus attracted dozens of Brixton’s residents who, having undergone decades of police harassment, thought the officers were arresting Bailey.

The hospital was just a short drive away and they pleaded he be taken immediately, but police policy had them wait for the ambulance. With Bailey growing weaker by the minute, the community wrestled him out of the police van and sent him to hospital in a passing cab. But Bailey’s safety didn’t mark the end of the clash. Fighting broke out between the police and Brixton community. Police cars poured in, but as numbers on both sides grew, the police eventually fled.

Tony Cealy first heard about the disturbance at five or six o’clock. “I had left school quite early, got home, and gone to my youth club,” he told me. “I was shocked to know that other young people were heading into Brixton to go and see what had happened.” Cealy lived on a council estate outside the city centre where local police officers were friendlier.

“They would often take off their jackets and play football with you,” he says, but central Brixton was a different story. There Cealy was stopped by police regularly, but it was the police vans in particular that he worried about. “They would stop, follow you, physically beat you, and ask questions afterwards,” he says.

Seeing Michael Bailey bleeding in the back of a police van, “even though the police were helping, it looked to those young people at the time that they were arresting him without taking him to the hospital,” Cealy says. “That got them upset and they started to retaliate.”

When the crowds eventually dispersed that night there was tension in the air. Something was about to happen in Brixton. Community leaders met with police and pleaded with them to deescalate the situation, but the next morning, on April 11, Operation Swamp resumed in full force.

Cealy was out shopping with his mum that afternoon. “I remembered that sort of feeling. There was a sense that something had happened last night,” he says. “There was a lot of people around at the time, more than usual on the streets.” Standing outside Woolworths he saw a group of young people yelling profanities and throwing things at the police. “I didn’t really know what had happened last night but it had started to flare up,” Cealy says. “It felt like something was going to kick off but you don’t know what and you don’t know when.”

Warzone.

The what and when was a stop and search just before five. A Black taxi driver was parked in his cab at the taxi-rank on Atlantic Road, something the police deemed suspicious. They searched the man and his cab for drugs, finding nothing, but word had already spread. Atlantic Road quickly filled with young people looking for action. Arguing started at the taxi-rank, followed by a push, followed by a punch, and moments later 20 police officers stormed the crowd. Brixton snapped.

Paddick had just sat down at his parents’ home in Sutton. “I put on the news and saw colleagues that I knew personally with blood streaming down their face,” he says. He phoned the control room and was asked to go in with any off-duty officers that could get to the area. “I was given the role of taking ten officers and clearing out Mayall Road, where buildings and cars were on fire.

“I can distinctly remember coming under attack from rioters – a hail of broken paving slabs and bricks,” he says. “We had six plastic shields and ten officers in rugby scrum formation. As we moved forward, they ran back, reequipped themselves, and then started throwing things at us again.” Though Paddick didn’t see it himself, over on Railton and Leeson Roads the first petrol bombs were being thrown. Masses of Brixton locals and police were taking turns to push each other back.

“The atmosphere was pretty much like being in a warzone,” Cealy says. He’d heard of the commotion and headed back into Brixton. The Woolworths he’d been to just an hour or two earlier was smashed open and looted. “It was scary,” he says. “Police officers couldn’t do anything because they were outnumbered on the high street. Down the side roads there was just lots more burning and shouting and mayhem. On the main streets there was pockets of youths and looters, settings things alight and turning cars over.”

Cealy lost the friend he’d gone into Brixton with and was caught up with a group of other young people. “We were in a mix of being chased by the police and also charging at the police, and that went on for what felt like the whole day,” he says. “It must have been a couple of hours of resting, charging at the police, and them charging at us.”

Taking a break on the corner of Ferndale Road, Cealy watched as some teenagers smashed open a Burton clothes shop. They jumped in, took what they could, and quickly dashed away, leaving a mess of shattered glass and scattered clothes on the ground. “And I stood there looking at this pink shirt that was glittering in the middle of the street,” Cealy says. It was just lying there, ignored by everyone but him.

“At one point I just ran out and picked up the shirt, and ran around the corner,” Cealy says, “and ran straight into a bunch of police who arrested me, started calling me names. They took the shirt from me and threw me in the van.” They berated him with threats of how much trouble he was in, that he’d be implicated for property damage and robbery and possession of stolen goods. “This is all on the floor of the van, where I’ve got some of the officers’ boots on my back. One was on my leg,” Cealy says. He was 15.

The police station wasn’t far, and Cealy arrived to see an older man covered in cuts and bruises, bleeding heavily from his face. “Oh my god,” he thought. “If that’s what happened to him I’d better keep my mouth shut.” There were older kids too, still being aggressive to the police officers who had them in handcuffs, and Cealy was shouted at by the desk sergeant demanding his details. “It was a very scary time for me,” he says. “After being charged I remember going down into the cells and hearing some of the screams of terror, and seeing blood on the walls.” He was kept in a cell with a wounded older man but only for half an hour until his mum arrived. She apologised for his behaviour, and “I then got taken home and got the beating of a lifetime.”

The dust settles.

Between the torched buildings, wrecked cars, and looted shops, more than £7.5 million in property damage was caused. Though commonly referred to as the Brixton riots, anyone from Brixton would first call it an uprising, “because enough was enough,” Griffiths says. “We’re not going to be pushed around, harassed, every day of our life. It’s going to give, and that’s what happened.” She sees it as a dark day in Brixton’s calendar, “because the Brixton I grew up in – vibrant with culture, music, friends – was burned to the ground because of despair.” Her one reassurance throughout the weekend was the sound of reggae music playing through the smoke. “That was what made me feel like reggae music was the music of the people. It was the music of resistance.”

Cealy headed back into Brixton with a friend the next day. “It was just burned out cars, buildings, shops,” he says. “So much more of the looted goods were on the floor and people were sort of scavenging, going through things. I remember seeing some of the shopkeepers sitting outside their shops, totally shocked with what had happened.” The pair’s exploring didn’t last long as his friend was arrested, something Cealy glossed over as if, and it was, a completely normal occurrence. He instead turned his attention to the elders of his community, who he saw talking to the police along Railton Road.

These conversations between Brixton’s community leaders and the police would become common in the attempt to repair their relationship, but the desire to make peace wasn’t immediate. Within the police, Paddick says, “the feeling was that we’d lost control of the streets and that we had to take it back, [by] being even more heavy handed than we were before.” Similar uprisings took place that summer, the biggest in Liverpool’s Toxteth and Manchester’s Moss Side areas, but it wasn’t until November that the country’s perspective on these events began to change.

Lord Leslie Scarman led an inquiry into the Brixton uprising, publishing his findings on November 25, 1981. Thatcher had already declared that “nothing justifies what happened,” dismissing any presence of racism. But Scarman disagreed. He shocked the nation by condemning the police as the problem, and urging the government “to provide useful, gainful employment and suitable educational, recreational, and leisure opportunities for young people, especially in the inner city.”

And Brixton did see some change. “It felt like there was a lot of talk about how they could do things differently now, certainly with our elder community leaders having those discussions with the police,” Cealy says. Though it wasn’t immediate, and wasn’t perfect, “you started to see things coming up from some of those discussions, like the Brixton Community Centre. So certain initiatives started popping up in the community based on the Scarman Report and the recommendations that came from that.”

Paddick sensed some change in the police as well. He had completed his college course and found particular meaning in the liberalising effects of education that Scarman mentioned. His final thesis was on the Brixton uprising, due a week before Scarman’s report was published. “We came to very similar conclusions,” he says. The academic assessing his work deemed it refreshingly critical, which was great until Paddick had his course review with the commander in charge of Operation Swamp, who demanded to know what refreshingly critical meant. “I said there had to be limits to law enforcement,” Paddick explains. “The impact on communities and the potential for disorder had to be balanced against the need to enforce the law.”

Perpetuity.

He returned to work in Brixton as a community police officer, patrolling the streets in uniform while trying to build bridges with the local community. “I loved it,” he says. “The combination of being involved in the riots, being at police college, producing my alternative Scarman Report – it all had a transformative effect on my view of policing.” Seeing things get a little better was therefore a huge relief, with initiatives like the meetings between police and community leaders. “So there was some improvement,” Paddick says. “But of course, it all kicked off again when inspector Douglas Lovelock accidentally shot Cherry Groce.”

In September 1985, police broke down the front door of the Groce family home in Brixton. 37-year-old Cherry Groce lived there with five of her six children, and she was upstairs at the time with her 11-year-old, Lee. Heading down to investigate the noise, Groce was shot in the chest by Lovelock. She lay on the floor bleeding while officers screamed at her, demanding the location of her oldest son, Michael, who was suspected of armed robbery and no longer lived there. Cherry would live the rest of her life paralysed before passing away in 2011 at 63-years-old, from kidney failure that was directly linked to the gunshot. The shooting triggered another uprising in Brixton.

And that is the bitter reality. The New Cross fire, 1981; Cherry Groce, 1985; Stephen Lawrence, 1993; Christopher Alder, 1998; Sean Rigg, 2008; Rashan Charles, 2017. The list goes on, “so when we look back at forty years on, what has changed?” Griffiths asks. If you talk to ten Black people, “how is it that our experience is the same?”

In Brixton today, though police are no longer as explicitly racist towards its Black community, the underlying racism is equally dangerous. “It’s moved from overt racism to covert racism,” Griffiths says. The government’s latest figures, for example, show that Black people are nine times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people. “Forty years on it’s more about the structural racism – the way institutions are set up to enable racism to still thrive,” she says. “At least overt racism I can see. Now they’re more subtle with it.

“If Britain wants to be the leading country in the world for inclusivity, a vibrant society, a better society, then it would do things differently, and not just roll out the same blueprint that has failed for hundreds of years,” Griffiths says. “It’s built on an out of date system that doesn’t work, because they’re not protecting and serving the most vulnerable people in our society.” She believes having coaches of culture is key in repairing British institutions, where people with the lived experience of social injustice can explain how to fix it. “Bring the people you’re trying to reach in to be part of the solution,” she says. “See them as experts. Treat them as equal to yourself.”

Cealy agrees, because “you’ve got people who run the system, and it works for them as white middle-class males. What they’re not doing is producing results that benefit people who don’t look like them.” He laments that Black people are still disproportionately stopped and searched and disproportionately being jailed. “Those things are still happening like they did 40 years ago,” he says.

The 2017 Lammy Review found that, while British people from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic backgrounds only make up 14% of the general population, they make up 25% of the prison population and 40% of young people in custody. Non-white people are also more likely to be arrested, more likely to be imprisoned for drug offences, and more likely to report negative experiences in prison.

“I think it’s got to involve all of the stakeholders from the beginning to really have that conversation, for the real change to not only come but be long lasting,” Cealy says, “It’s just difficult; it’s really difficult. But we can’t give up, can we?”

Somehow Cealy hasn’t given up, nor Griffiths. Looking back 40 years, “For some people it’s painful, it’s a trauma,” she says. “People have lost their lives at the hands of the police and there’s no justice. They march for years and there’s no justice. It is a very painful experience.” It would’ve been easy for Griffiths to purely be angry, but she instead uses her experience to create change. “You either stand for something,” she says, “or you fall for anything.”

If that change doesn’t come though, Paddick expects there might be a repeat of what happened in Brixton 40 years ago. “You’ve got this perfect storm of the police going back to exercising force in order to reduce crime, rather than working with communities,” he says, “and a government that is facilitating that and encouraging it.” Paddick and his colleagues who are campaigning for a more equal Britain, “we’re concerned that history could be repeating itself,” he says, “in terms of the misuse of stop and search and the impact on the Black community.”

Griffiths shares these concerns. “Until we no longer judge by the colour of our skin and where we come from there’s going to be war,” she says. “We want to be happy; we don’t want to be fighting. But until there’s peace there’s going to be war. And it’s not because I’m advocating it, it’s because, at the end of the day, people are not going to keep being pushed around, called names, harassed by the police every day,” she says. “Something’s going to give.” In the words of Bob Marley, there will be war in the east, war in the west, war up north, and war down south.

Feature Image Credit: Kim Aldis (CC BY-SA 3.0)